Experts were divided over why violence rose in consecutive years for the first time since 2006.

_______________________

President Trump and Attorney General Jeff Sessions have said repeatedly that the nation is in the grip of a crime wave that requires more arrests and harsher penalties, including for nonviolent crimes like drug possession.

Mr. Trump, in his Inaugural Address in January, spoke of “American carnage” to describe the nation’s rate of killings, and Mr. Sessions has directed prosecutors to more aggressively charge those arrested, while blaming illegal immigration for much of the rise in violence. Criminologists, police officials and others who study crime say that is untrue.

The Trump administration’s tough-on-crime strategy comes after more than a decade of criminal justice reforms at the federal, state and local levels that have proved popular with both liberals and conservatives.

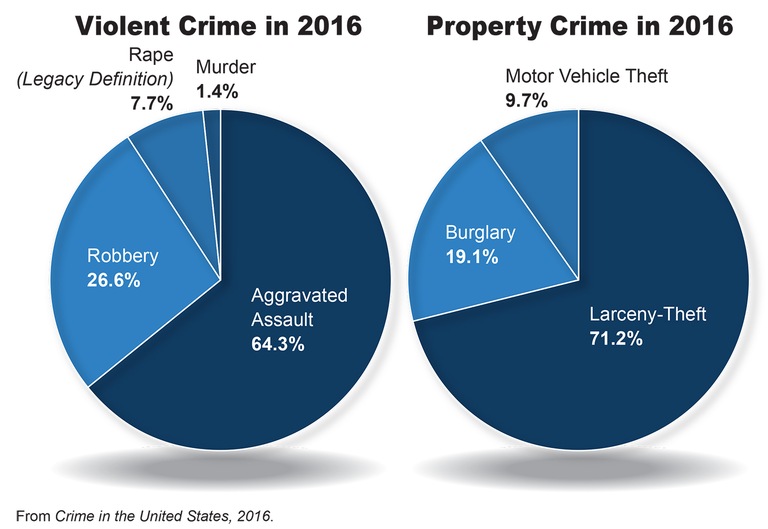

Critics of the administration’s criminal justice policies point out that despite the recent increases in violent crime, since 1971 there have been only five years with lower violent crime rates than 2016.

“There are pockets of increased violence across the country that demand an increased response from all levels of government,” said Adam Gelb, director of the public safety project at The Pew Charitable Trusts. “But there is no indication that we’re in the midst of a crime wave, and no justification to return to the failed policies of the past.”

He added: “What’s going on? No one really knows. And if someone says they do know, you ought to be deeply suspicious. It’s too early to tell anything.”

Among the reasons cited for the increase are a profusion of handguns, poverty and social isolation, warring gangs involved in the drug trade, and police officers who are questioning fewer people and making fewer arrests for fear of being criticized by superiors and civil rights groups.

Each hypothesis has its detractors. But one theory that has gained traction of late is that violence has increased as police legitimacy has been questioned after the fatal police shootings of unarmed African-Americans. The shootings, many of which have been captured on video over the last three years, have been widely disseminated via the news media and on the internet.

Proponents of the theory maintain that in cities where police departments treat citizens with disrespect and engage in brutality, residents will eventually stop cooperating with the police, which will diminish officers’ ability to solve crimes. The result, according to the argument, is that the most violence-prone people in a particular area will be free to continue committing crimes with little fear of arrest.

“The question really is, what is different now from 15 years ago in terms of why crime has increased?” said John K. Roman, a criminologist at the University of Chicago. “And the only thing that has changed is the distrust between heavily policed communities and local police. It’s not a coincidence that cities that have crime increases have also had problems between communities and the police.”

Among the cities that have experienced recent upticks in murder coupled with questionable police shootings that prompted rioting or other civil disturbances are Chicago, Baltimore, Charlotte, St. Louis and Milwaukee. But other cities where there have been significant increases in homicides in recent years, including Las Vegas and Memphis, have been largely free of public anger in response to fatal police shootings.

In 2016, Chicago again led the nation in murders with 765 — more than double the 335 people killed in New York, which has more than 5.8 million more people than Chicago.

In Chicago and elsewhere, murder victims, as well as those arrested on murder charges, were disproportionately young, African-American and male, according to the F.B.I. records and data from local law enforcement agencies. The overwhelming weapon of choice was a firearm, responsible for four of five killings in 2016.

And although large cities — those with populations of more than a million people — saw homicides rise by 20.3 percent, and all violent crime increase by 7.2 percent in 2016, the trend toward greater violence was felt in cities and towns of all sizes. In towns with populations of fewer than 10,000 people, for instance, murders rose by 8.4 percent, according to the F.B.I. data.

Current data suggests, however, that violence may be tailing off in 2017, at least moderately.

In an analysis of the nation’s largest cities, the Brennan Center for Justice at the New York University School of Law projected that violent crime would drop this year by 0.6 percent and that the overall crime rate would fall by 1.8 percent.

Continue reading the main story