A United Nations summit approved on Monday a landmark global deal to protect nature and direct billions of dollars toward conservation but objections from key African nations, home to large tracts of tropical rainforest, marred the final passage.

The Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, reflecting the joint leadership of China and Canada, is the culmination of four years of work toward creating an agreement to guide global conservation efforts through 2030.

The countries attending the U.N.-backed COP15 biodiversity conference had been negotiating a text proposed on Sunday and talks addressing the finer points of the deal dragged on until Monday morning.

Delegates were able to build consensus around the deal’s most lofty target of protecting 30% of the world’s land and seas by the decade’s end, a target known informally as 30-by-30. However, questions around the funding contributions from developed nations to developing countries appeared unresolved as the delegates gathered to consider adoption of the text.

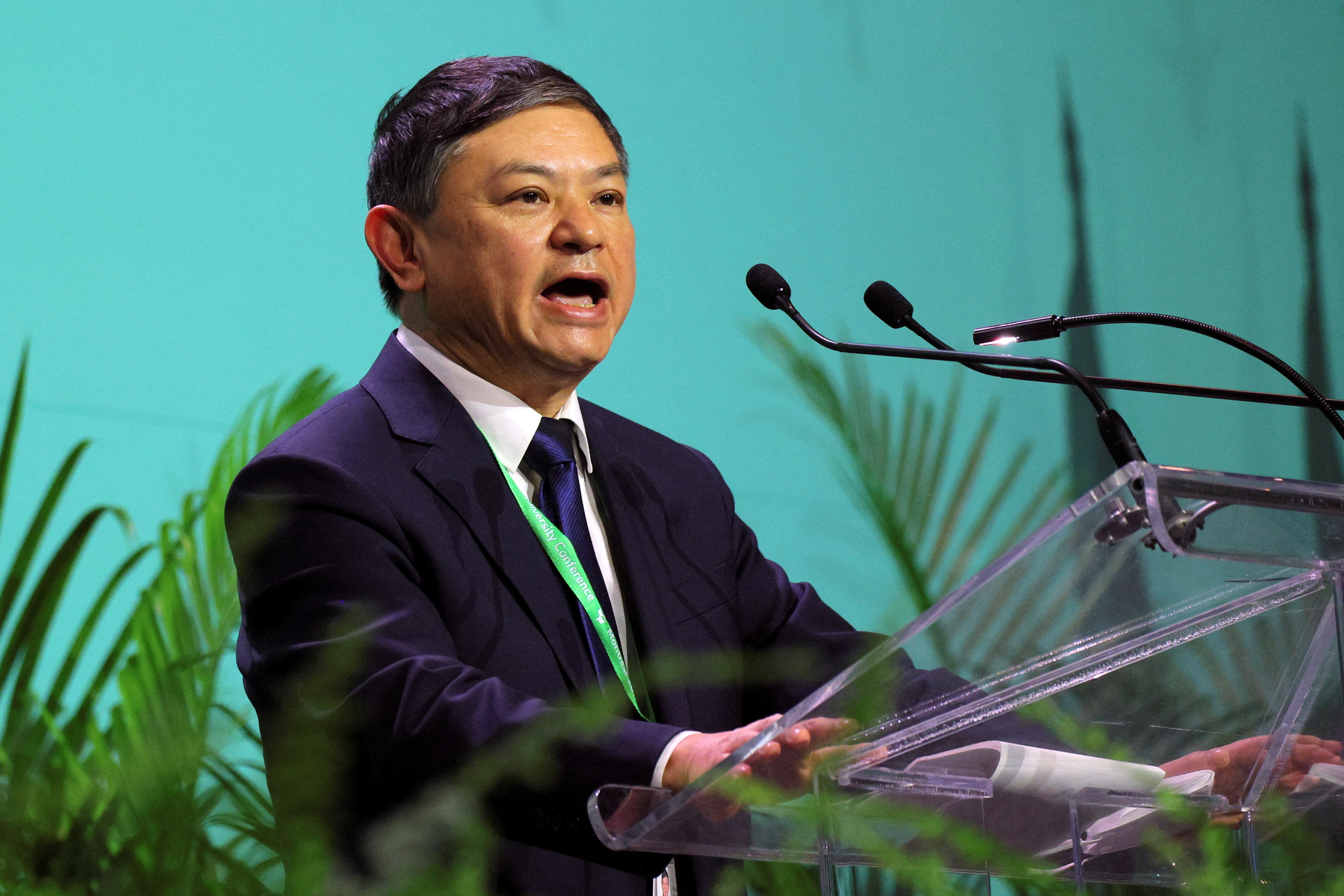

With China holding the COP15 presidency, Minister of Ecology and Environment Huang Runqiu appeared to disregard objections from the delegation of the Democratic Republic of Congo, lowering the gavel and declaring the deal passed only minutes after they said they were not able to support the deal.

“The parties which are developed nations should provide resources to parties which are developing,” the Congolese representative said through a translator.

Huang then acknowledged Mexican remarks supporting the final agreement and declared shortly after 3:30 a.m. (0830 GMT) that the deal was adopted, drawing outraged comments from other African delegations.

A representative from Cameroon said through a translator that the agreement was passed by force of hand.

A Ugandan representative declared that they did not accept the spirit and the manner at which the gavel fell and requested to put on record that Uganda did not support the procedure, invoking fraud.

A closing meeting will be held later on Monday.

In addition to supporting 30-by-30, the deal also directs countries to allocate $200 billion per year for biodiversity initiatives from both the public and private sectors

Developed countries will provide $25 billion in annual funding starting in 2025 and $30 billion per year by 2030.

The deal, which contains 23 targets in total, replaces the failed 2010 Aichi Biodiversity Targets that were intended to guide conservation through 2020. None of those goals were achieved, and no single country met all 20 of the Aichi targets within its borders.

Unlike with Aichi, the deal contains more quantifiable targets — such as reducing harmful subsidies given to industry by at least $500 billion per year — that should make it easier to track and report progress.

More than 1 million species could vanish by century’s end in what scientists have called a sixth mass extinction event. As much as 40% of the world’s land has been degraded, and wildlife population sizes have shrunk dramatically since 1970.

Investment firms focused on a target in the deal recommending that companies analyse and report how their operations affect and are affected by biodiversity issues.

The parties agreed to large companies and financial institutions being subject to “requirements” to make disclosures regarding their operations, supply chains and portfolios – but the word “mandatory” was dropped from previous drafts.