On Dec. 13, 2022, the Israeli Supreme Court published a 51-page judgment in Kohelet Forum v. Prime Minister, providing reasons for its Oct. 23, 2022, decision to greenlight the Israel-Lebanon Maritime Delimitation Agreement. (The agreement was finalized and announced on Oct. 27, 2022.) In its judgment, the court considered and rejected three challenges to the agreement raised by the petitioners: that the agreement involved a transfer of sovereignty over Israeli territory and should have therefore been put to a national referendum; that, due to its status as a caretaker government, the Government of Israel (GOI) was legally barred from concluding the agreement; and that the GOI was required, by virtue of a constitutional usage or custom, to bring the agreement to a vote before the Israeli Knesset. The judgment offers a number of interesting insights on the interplay between international law and Israeli constitutional law, including a first-of-its-kind analysis of the application of a Basic Law, requiring the holding of a referendum in connection with territorial concessions, to maritime delimitation questions.

On Dec. 13, 2022, the Israeli Supreme Court published a 51-page judgment in Kohelet Forum v. Prime Minister, providing reasons for its Oct. 23, 2022, decision to greenlight the Israel-Lebanon Maritime Delimitation Agreement. (The agreement was finalized and announced on Oct. 27, 2022.) In its judgment, the court considered and rejected three challenges to the agreement raised by the petitioners: that the agreement involved a transfer of sovereignty over Israeli territory and should have therefore been put to a national referendum; that, due to its status as a caretaker government, the Government of Israel (GOI) was legally barred from concluding the agreement; and that the GOI was required, by virtue of a constitutional usage or custom, to bring the agreement to a vote before the Israeli Knesset. The judgment offers a number of interesting insights on the interplay between international law and Israeli constitutional law, including a first-of-its-kind analysis of the application of a Basic Law, requiring the holding of a referendum in connection with territorial concessions, to maritime delimitation questions.

Background Developments

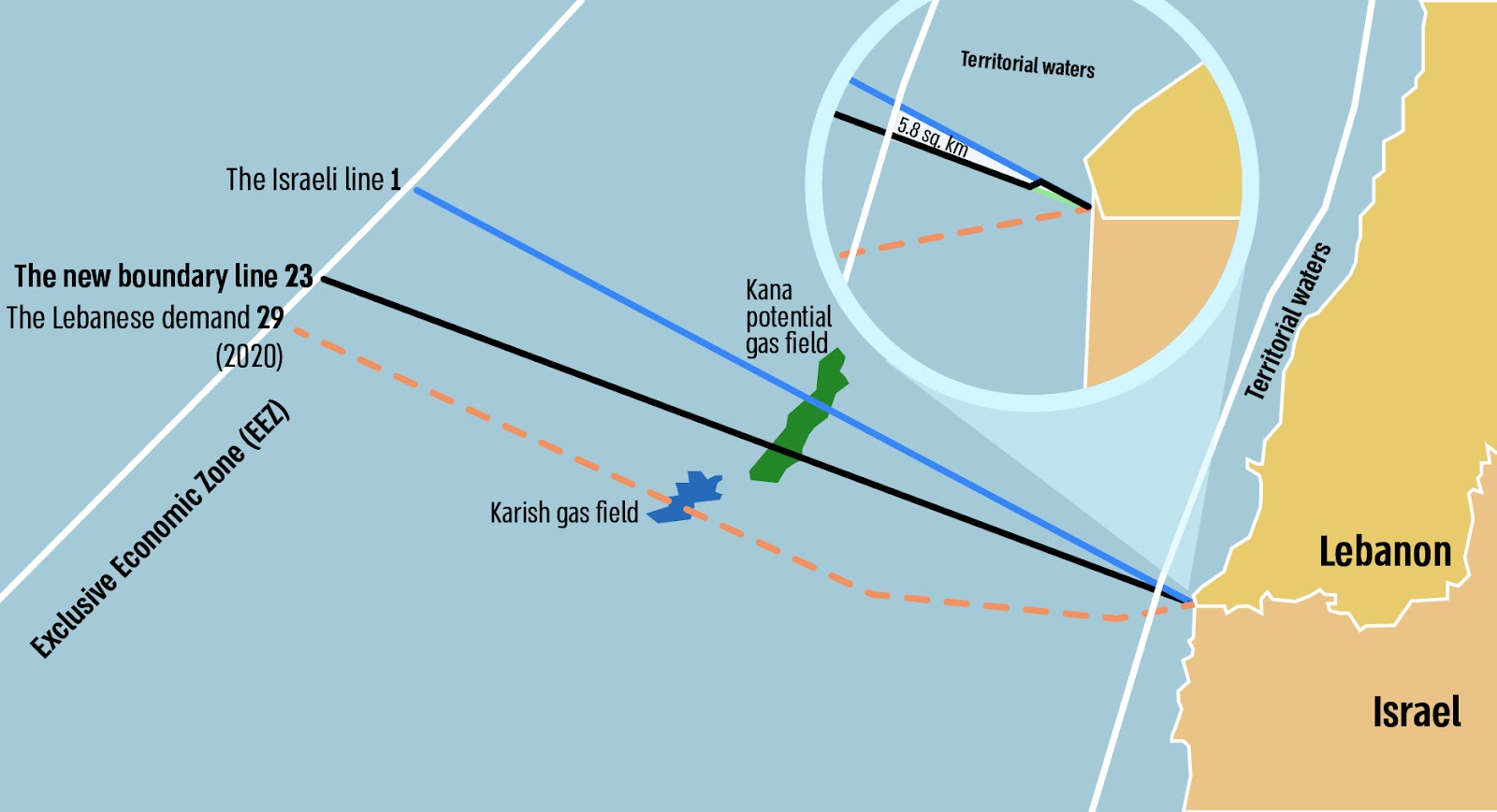

Israel and Lebanon share a land and maritime border, but the boundary line on land and at sea has remained for many years contentious and mostly undelimited. In 2000, Israel unilaterally demarcated a 7.5-kilometer-long security line perpendicular to the de facto land border on the coast through the placing of 10 buoys (that is, the buoys line), and deployed its navy to prevent vessels from crossing that line in proximity to the coast. In 2010, Lebanon deposited with the United Nations a set of maritime boundary coordinates, representing its claim to maritime zones in the boundary area (referred to below as Line 23 or the Southern Lebanese Line). The following year, in 2011, Israel deposited with the U.N. its own coordinates representing its counterclaim to Lebanon’s coordinates (namely, Line 1, which effectively constituted a seaward extension of the buoys line). The maritime area locked inside the triangle formed by Line 1 (the Northern Israeli Line), Line 23 (the Southern Lebanese Line), and the beginning of the Cypriot maritime zone (which is parallel to the Israeli/Lebanese coastline, running approximately 130 nautical miles from that coast) comprises some 870 square kilometers.

Following over a decade of negotiations, facilitated by U.S. mediation and featuring many delays and interruptions, Israel and Lebanon reached the Oct. 23, 2022, agreement on maritime boundary delimitation. This development took place against two competing plans from Israel and Lebanon. Israel has plans to commence the commercial exploitation of a natural gas field (called Karish), south of Line 23, which nonetheless falls inside an area of the Mediterranean Sea that Lebanon claimed at one stage of the negotiations (when it presented a revised line going considerably beyond the line it deposited with the U.N.). Lebanon has plans to commence exploration of another natural gas field (called Qana) that is north of Line 23 but is potentially traversed by Line 1. According to the agreement, Israel would accept Line 23 but would receive a fixed percentage from the proceeds from the Qana field (a separate agreement was concluded in November 2022 between Israel and the private energy companies involved in the exploitation of the Qana field). As part of the deal, the parties agreed to maintain, until the time in which a land boundary delimitation agreement would be concluded, the status quo in and around the first 5 kilometers of the buoys line, effectively accepting Israel’s security control of the area south of that line. The parties furthermore agreed that the agreement established a permanent and equitable resolution of their maritime dispute.

The Institute for National Security Studies (INSS) has created a map of the newly agreed-upon maritime order:

New Israeli-Lebanese Maritime Border

Image created by The Institute for National Security Studies (INSS). Reprinted with permission.

Since the agreement was finalized in the weeks running up to the Israeli general elections, which occurred on Nov. 1, 2022, its conclusion became part of the election conversation. Opposition leader Benjamin Netanyahu (who has since returned to power) accused the GOI of unjustifiably surrendering Israeli maritime areas and economic assets to Lebanon, an enemy state, and to Hezbollah—which Israel and other states consider a terror organization, and which exercises considerable influence on political affairs in Lebanon. By contrast, then-Prime Minister Yair Lapid proclaimed the agreement to be a historical achievement of his government that would increase stability and economic prosperity in the region.

The Litigation

Following media reports concerning the impending conclusion of the agreement, a number of public interest groups brought petitions in the first half of the month of October 2022 to the Israeli Supreme Court against the GOI, the Knesset, and a number of government ministers, challenging the authority to conclude the agreement. The two initial petitioners—the Kohelet Forum and Lavi Organization (two right-wing civil society groups)—were joined by a group of private citizens and by Itamar Ben Gvir’s Otzma Yehudit (also known as Jewish Power, an extreme right-wing party represented in the Knesset). Their request to obtain interim injunctions against the GOI were rejected by the Supreme Court, and following a televised hearing held on Oct. 20 before a panel of three justices, their petitions were rejected on Oct. 23 by a unanimous decision of the panel of three justices assigned to the case. On Oct. 27, the GOI and Lebanon finalized the agreement.

The court’s judgment was published on Dec. 13, 2022 (the Oct. 23 decision was announced without an accompanying opinion from the court). It addressed the three main challenges presented by the petitioners: that the agreement involved a transfer of sovereignty over Israeli territory and should have therefore been put to a referendum; that, due to its status as a caretaker government, the GOI was legally barred from concluding the agreement; and that the GOI was required, by virtue of constitutional usage or custom, to bring the agreement to a vote before the Israeli Knesset. In an unusual manner, the three justices divided between them the task of explaining the court’s position on the three questions at issue and expressed agreement with the explanations provided by each other.

The Inapplicability of the Referendum Basic Law

The first, and probably most interesting, challenge made by the petitioners related to the interplay between the agreement and Israeli constitutional law on the transfer of sovereign territory. As part of an effort by right-leaning members of the Knesset to render it more difficult for the GOI to agree on territorial concessions in future peace deals, the Knesset passed in 1999 a law that was amended in 2010 (the formal title of the law is “Administration and Law Procedures (revocation of application of law, jurisdiction and administration) Law”), providing that a GOI decision to revoke the application of Israeli “law, jurisdiction and administration” with respect to a territory to which it applies must be approved by a majority of at least 61 members of the Knesset and a referendum or, alternatively, by a vote of 80 (out of 120) members of the Knesset. The Knesset reiterated this in 2014 when it passed the Basic Law: Referendum, which repeated the language found in the 2010 law, while affording it with a constitutional status.

The petitioners claimed that the agreement involved the transfer of sea territory from Israel to Lebanon and that, as a result, it fell under the terms of the Basic Law: Referendum. To make this argument, the petitioners relied on the Territorial Waters Law (1956), which resulted in extension of Israeli law to the 12 nautical miles area adjacent to the coast, and on the Undersea Water Lands Law (1953), which proclaimed the coastal continental shelf as “State territory.” The Attorney General’s Office claimed, by contrast, that maritime areas outside the territorial sea are not part of the sovereign territory of the State of Israel (although Israel has certain sovereign rights in respect of them) and that the northern boundary of the territorial sea has not been conclusively delimited before the agreement was concluded.

Justice Uzi Vogelman rejected the petitioners’ claims regarding the application of the Basic Law: Referendum to the agreement. He held that the Basic Law was enacted with the specific aim of limiting the power of the GOI to transfer territories in East Jerusalem and the Golan Heights—areas in relation to which Israel clearly and explicitly applied its laws through Knesset legislation and/or GOI decisions. He did not consider the maritime areas found outside Israel’s territorial sea to meet a comparable “clear and explicit application” standard, given the ambiguity of existing legislation and the lack of sovereignty in economic waters (exclusive economic areas and continental shelves) under customary international law. (Note that Israel is not a party to the 1982 U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea, but it regards most of the convention’s provisions as customary in nature.) Whereas Vogelman was willing to consider the territorial waters as falling under the Basic Law, he accepted the GOI’s position that Line 1 was submitted to the U.N. merely as a negotiating position and not as a conclusive act of demarcation of the outer limit of Israeli territory for Israel law purposes. In effect, he noted that, beyond the first 5 kilometers of the buoys line, Israel did not enforce its laws north of Line 23. Hence Vogelman reasoned that the small territorial sea area affected by the agreement (the area between the relevant segments of the two lines, located 3-12 miles from the coast; a gap averaging 300 meters in breadth) is not de jure or de facto subject to Israeli law.

The Powers of a Caretaker Government

Israeli Supreme Court President Esther Hayut addressed in her opinion the second challenge raised by the petitioners, pertaining to the powers of a caretaker government. After new elections were called on June 30, 2022, the outgoing government continued to serve as a caretaker government—which under the Israeli public law jurisprudence means a government with limited powers. According to the Supreme Court’s case law, it would be inappropriate for such a government to make appointments or adopt measures in order to bind the next government or to sway the elections. As a result, the court has held that a caretaker government must exercise its powers with moderation and restraint. Still, the government might justifiably—and, at times, even be required to—take measures that serve a vital public interest even before the elections, so as to avoid creating a decision-making vacuum.

In the case at hand, Hayut accepted the GOI’s position that the conclusion of the agreement before the elections served a vital and time-sensitive public interest. She noted that the government was presented with classified reports composed by Israeli security agencies (which the court also reviewed ex parte, with the consent of the parties to litigation), which identified a unique “window of opportunity” for concluding the agreement in light of political developments in Lebanon (presumably the end of President Michel Aoun’s term in late October 2022) and overriding security considerations (presumably Hezbollah threats to attack the Karish natural gas field, should extraction commence by Israel without an agreement). Against these facts, and in light of the broad discretion that the GOI enjoys in the field of foreign relations and national security (which extends mutatis mutandis to a caretaker government), Hayut held that there were no grounds for judicial intervention.

Approval of the Agreement by the Knesset

Justice Noam Sohlberg dealt in his opinion with the third objection raised by the petitioners pertaining to the role of the Knesset in approving international agreements. According to Israeli constitutional law, the GOI is competent to sign and ratify international agreements (this is pursuant to the British model, which associates such powers with the prerogatives of the Crown). Under the relevant Knesset and GOI by-rules, there is an obligation to deposit with the Knesset international agreements two weeks prior to their ratification (unless exceptional reasons of urgency or secrecy preclude this). During that time, different Knesset committees and the Knesset plenary may discuss the pending agreement. Still, the GOI has tended to bring important political agreements, such as peace agreements, to a vote of approval before the Knesset. There is some academic literature claiming that this practice amounts to a binding “constitutional usage” or “custom.”

Sohlberg noted that, in the case at hand, the GOI deliberated on whether or not to submit the agreement for Knesset approval and decided against it, citing that the classified reports on which it relied when supporting the agreement would not be available to all Knesset members (they can be presented only in a security-cleared Knesset subcommittee meeting behind closed doors). Under these circumstances, it opted for pursuing the standard two weeks deposit track (which involved, inter alia, a subcommittee discussion). Sohlberg held that, in following this path, the GOI was exercising its lawful discretion. As for the petitioners’ claim that the government should follow past precedents and submit the agreement to the Knesset for approval, Sohlberg was of the view that practices of past governments do not bind the existing GOI (or, in other words, that there is no established legal doctrine of binding custom generated by past parliamentary practices). In any event, he opined that past practice on submitting important agreements to a vote did not generate clear criteria as to what constitutes an “important agreement” that would merit Knesset approval. It is noteworthy in this regard that the 2010 maritime delimitation agreement between Israel and Cyprus was not brought to a Knesset vote. Having found no basis in law for requiring the GOI to submit the agreement to a vote by the Knesset, Sohlberg rejected this part of the petitioner’s case as well.

Judicial Conservatism in Support of Progressive Foreign Policy?

The proceedings in Kohelet Forum represent an interesting reversal of roles. Conservative groups that have often criticized the court for excessive judicial activism, including broad construction of constitutional instruments in ways that limit the power of the legislative and executive branches, have called on the court to do exactly that: to review a decision placed squarely within the government’s power to conduct foreign policy and protect national security. It is also interesting to note that the three justices on the panel acted in unison to reject the petitions, notwithstanding the fact that they have greatly diverged in the past on questions of judicial activism. (Sohlberg is considered among the most conservative justices on the court and Vogelman among the most activist of justices.) Their joint decision seems to underscore that, despite its tradition of expansive judicial review, the court is still apprehensive about interfering with high-stakes foreign policy and national security matters, and does not wish to assume responsibility for any political or security fallouts that might have ensued from the derailing of the agreement.

The judgment also offers a first-of-its kind engagement with the Basic Law: Referendum, which has not received much attention until now in Israel and beyond. Such limited attention can be explained by the lack of any serious peace talks vis-a-vis Syria or the Palestinians that might result in the transfer of territory currently subject to Israeli law. It could also be explained by the assumption that, if push comes to shove, the GOI will amend or abrogate the Basic Law (a simple majority of 61 out of 120 members of the Knesset may achieve that). The Israel-Lebanon agreement, however, presented a unique case in which it was plausible to argue that a transfer of territory governed by the Basic Law was being contemplated, without there being a realistic option of amending the Basic Law given the collapse of the governing coalition (a factor that can also explain the reluctance to bring the agreement to a Knesset vote). The approach that the Supreme Court took for this agreement—a narrow interpretation of the scope of application of the Basic Law, limiting its application to territories clearly and explicitly subject to Israeli law—may reflect unease on the part of the court with the institution of a national referendum (Israel has never held a national referendum, on any issue), as well as concerns about the implications for the government’s ability to effectively conduct foreign policy and protect national security if it were to operate under an overly tight constitutional straightjacket.

Finally, it is noteworthy that the court conducted its analysis of the legal status of the different maritime areas in relation to which Israel has legal rights in light of customary international law rules on sovereignty rights at sea (reading down the terms of the Undersea Water Lands Law accordingly). This implies that although there is no clear doctrine of interpretive compatibility between Israeli constitutional law and international law, the content of the latter significantly informs the former.

O

O