In his 1946 elegy the poet Aaron Zeitlin mourns a world that has disappeared. “My Warsaw is not being rebuilt,” he writes. “My Warsaw remains destroyed forever.”

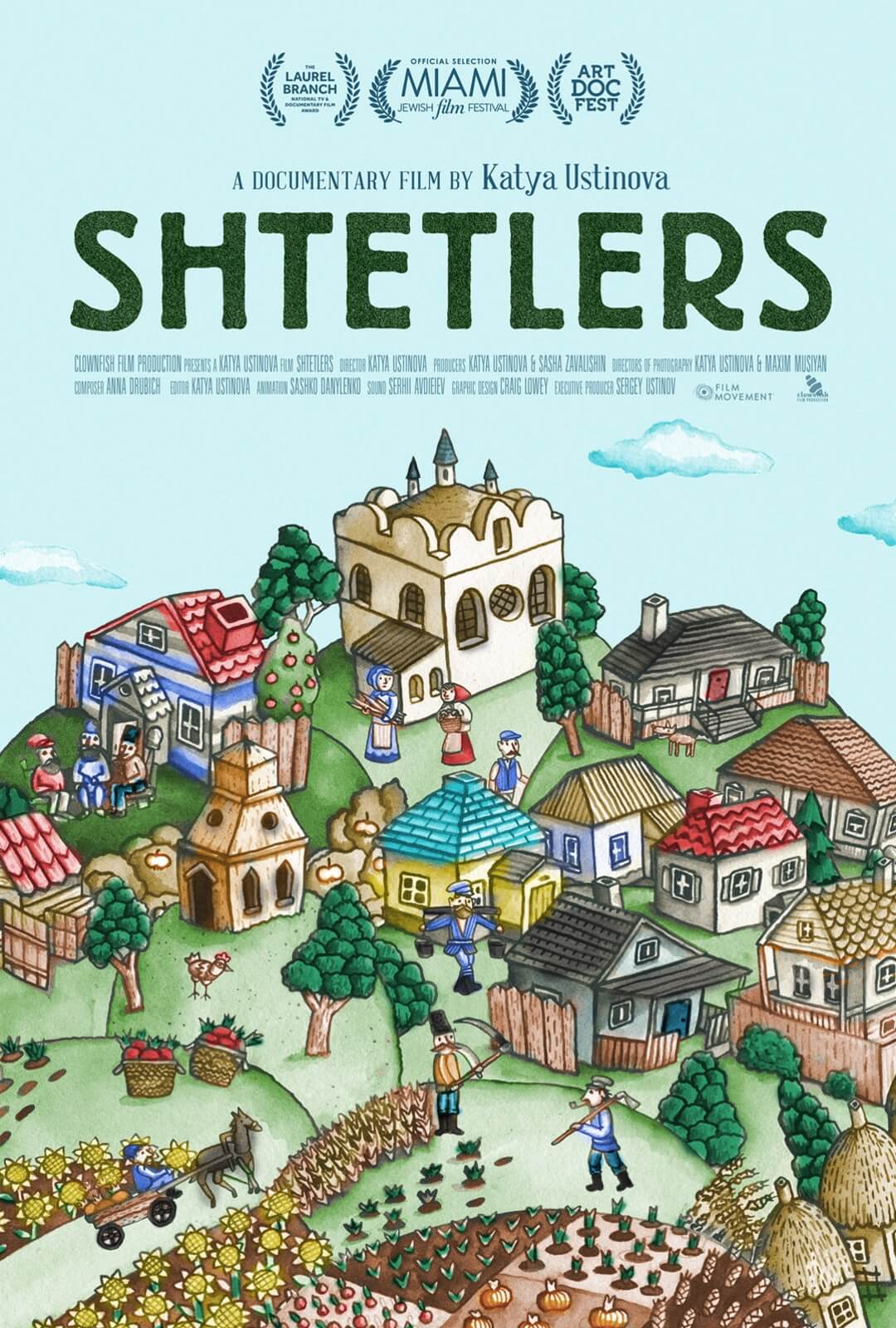

The young director Katya Ustinova reveals this destroyed world in her documentary “Shtetlers,” which begins streaming on Feb. 3 on Apple TV. The world that the film portrays, however, is not one of big cities like Warsaw. It’s about the shtetls, the small formerly Jewish towns in Ukraine and Moldova, now overgrown with moss, half-collapsed — and without any Jews at all.

Ustinova’s movie, like Zeitlin’s poem, is soft spoken. It has almost no music. The sadness is apparent, even without any dramatic filmic choices or scenes of great suspense. We feel the loss in the details. Sunken steps, hardly visible under overgrown wild grasses. A mezuzah on a wall, painted over in the white color of the wall, in a former Jewish home now occupied by non-Jewish couple. Someone’s father’s dusty hat, left behind years ago in the home of his youth in the tiny Bessarabian village Tîrgul Vertiujeni.

The hat lies on a windowsill, but the window has no glass. The person who directs the cameras to focus on the hat is Slava, one member of the film’s touching ensemble of nine “shtetlers.” We see them in their homes today in Eastern Europe, Jerusalem, Brighton Beach and Philadelphia. Many of them lived in their birth towns for years after the Holocaust, during the Soviet period. Among these narrators, there are some non-Jews who still live in these Jewish towns of a previous era.

“This used to be our living room,” says Slava in Russian, as he steps into a ruined house, with scattered pieces of wood on the floor. “Just like this house, my Yiddish is no longer there. The whole culture of the shtetls doesn’t exist anymore.”

But you can still hear the echoes of that culture, through the stories of the former inhabitants. They recount stories about their youth, their former communities and murdered families, and their livelihoods after the Holocaust. Even though most of them are now old and gray, they infuse the movie with life and color.

Another person in the film, Sofia, who lives in Philadelphia today, delights the audience as she bakes a savory matzah kugel. This was the exact dish that a non-Jewish woman, Nadya, baked in a previous scene. Nadya, a Ukrainian farmer, still lives in her old shtetl, where she learned the recipe from her former Jewish neighbors, whom she recalls affectionately.

While making the babka, Sofia cooks gefilte fish — the authentic traditional version, with spoonfuls of minced fish stuffed into the fish skin and then roasted. At one point, as she has trouble skinning the fish, she jokes: “Look, two stubborn women, the fish and me.” Later, while removing the fish from the oven, she addresses it as “Princess.”

Both she and the other elderly Jews in the movie still have rich stores of that sense of humor characteristic of the shtetl. And despite the fact that they are all scattered around the globe, the old shtetl culture lives within them. It lives in spite of the violent, horrific rupture in the world of the shtetl. It’s like the old prewar trees that you see in the movie, still growing among the ruined houses and tombstones. They have deep roots.

In Zeitlin’s last stanza, he predicts the future of his loved ones in Warsaw, and their culture:

The silent Kaddish will die

With us together — and everything

Will, like an old song,

Be forgotten.

In many ways, Zeitlin is right. Much is indeed forgotten. It is why Ustinova’s film, with its candid narrators, possessed of deep feelings and strong memories, is such a worthy contribution.

The post Film depicts present-day European shtetls where Yiddish once thrived appeared first on The Forward.