Australia will introduce rules to increase transparency in ministerial appointments after an inquiry into secret ministerial appointments by then Prime Minister Scott Morrison found they corroded public trust in government.

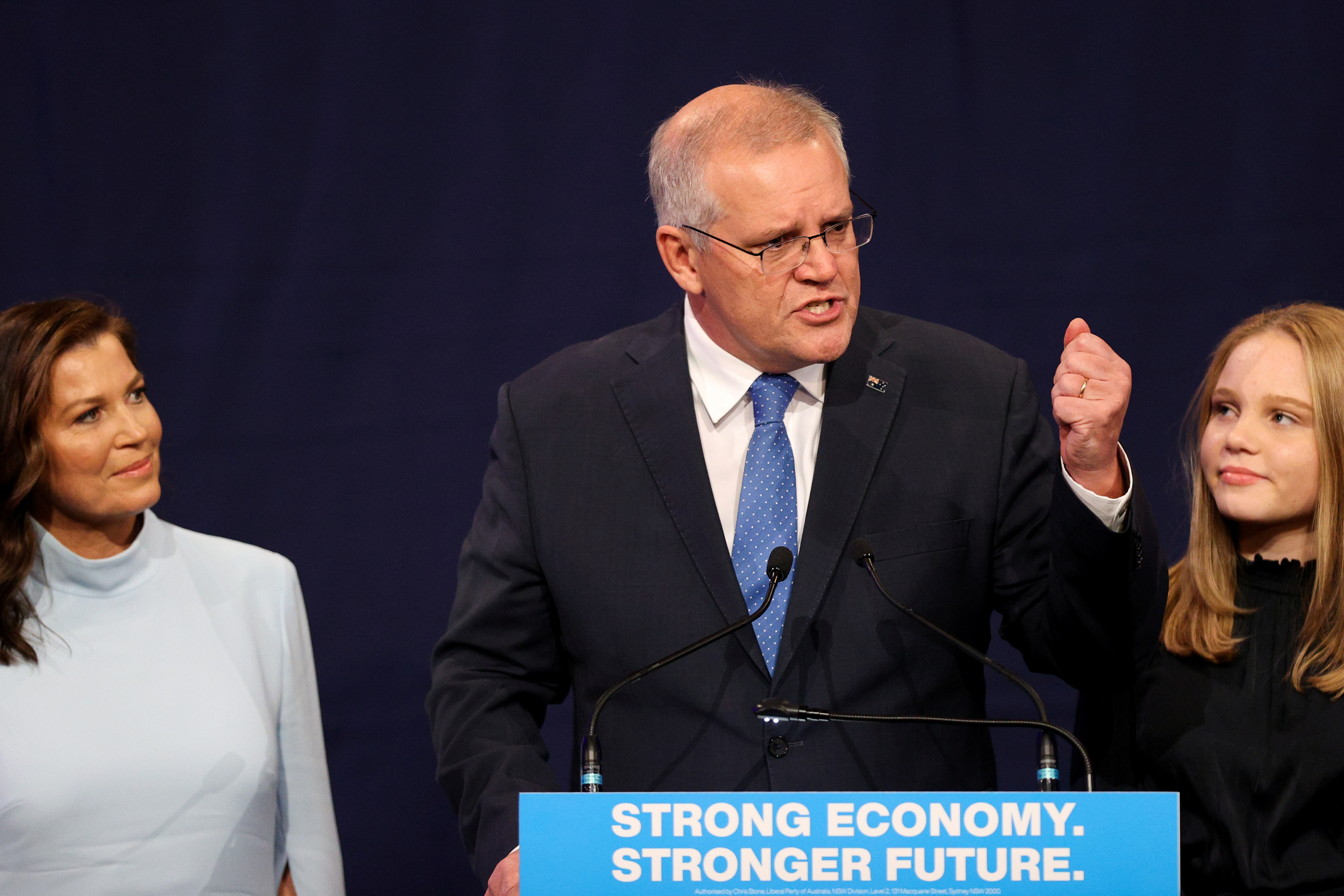

Morrison, who lost power in a general election in May, secretly accumulated five ministerial roles during the coronavirus pandemic: health, finance, treasury, resources and home affairs.

Three ministers later said they did not know they were sharing power with Morrison.

An inquiry led by former High Court judge Virginia Bell found the appointments likely hurt public confidence in government. Echoing comments from the solicitor general, Bell said in a report issued on Friday, that the lack of parliamentary accountability undermined responsible government.

“Once the appointments became known, the secrecy with which they had been surrounded was corrosive of trust in government,” Bell said.

Morrison said earlier the appointments were necessary during the pandemic to ensure continuity and as a precaution in case a minister was incapacitated. But the report raised doubts on both counts, arguing for example, that acting ministers could have been quickly appointed if needed.

In a statement shortly after the report was issued, Morrison noted the criticism but defended his actions as lawful and said he would continue in parliament.

“As Prime Minister my awareness of issues regarding national security and the national interest was broader than that known to individual Ministers and certainly to the Inquiry,” he said in a Facebook post.

“This limits the ability for third parties to draw definitive conclusions on such matters.”

Bell recommended six changes, including legislation requiring public notice of ministerial appointments.

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese said his government would adopt all six of the recommendations.

“We’re shining sunlight on a shadow government that preferred to operate in darkness. A government that operated in a cult of secrecy and a culture of cover-up,” Albanese told a news conference after the release of the report.

Bell noted that because Morrison’s extra powers had only been exercised once, the implications of the appointments were limited.

While calling it “troubling” that then senior official Phil Gaetjens, who prepared briefs on the appointments, did not push for more disclosure, the inquiry said responsibility for the decisions lay with the then prime minister.

Morrison communicated with the inquiry through an attorney.