The story of Hanukkah, of Jews triumphing over their persecutors, stokes Jewish pride — and also, for a fifth grade class in Georgia, offers a lesson in the science of combustion.

Robbie Medwed, a Judaic studies teacher at Atlanta’s The Epstein School, recently guided his students in a Maccabee-inspired experiment.

Partnering with a science teacher at the school, Aly Clement, he prepared a hands-on lesson that would teach both Judaics and chemistry. Their inquiry inspired the Forward to pursue other scientific questions about menorahs and oil-burning. But first, what happened in that Atlanta classroom when Medwed and Clement asked their students to find out what kind of oil burns brightest and longest?

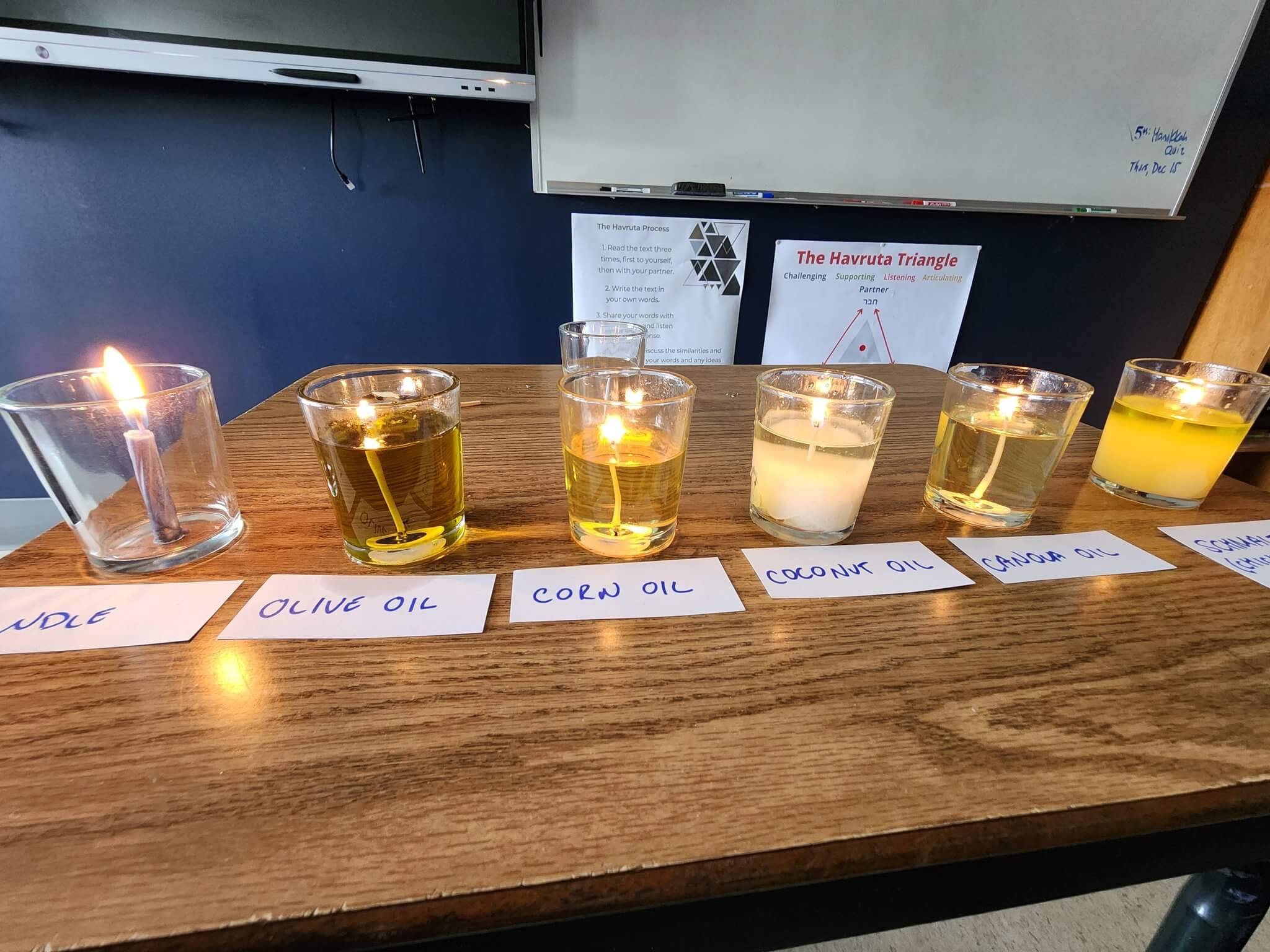

To find out, the teachers poured six different substances into six different glasses and inserted wicks so that they had candles made from olive oil (the traditional oil for Hanukkah menorahs), corn oil, coconut oil, canola oil, wax and chicken fat, known in Yiddish as schmaltz. First the students figured out which of the oils was most dense, by dropping marbles into the oils to see how fast they sank. Then, they lit them, with some hypothesizing that a denser oil would make for a brighter candle.

Not so!

“The oil that was the most dense was not the brightest and it actually didn’t burn the longest,” Clement said.

The brightest burning oil? Corn oil. The longest-lasting? Undetermined. For safety reasons the candles had to be extinguished when class was over, skewing the results.

As with many science experiments, some unexpected discoveries were made. When the schmaltz candle was lit, Medwed was “ready for the whole hall to smell like chicken soup, but it didn’t.”

When Medwed posted the experiment to Twitter, it racked up almost 1,000 likes (and a few complaints that the ancient priests did not have access to coconut or canola oil).

Medwed said the experiment didn’t just help them to grasp the concepts of volume and mass, but also gave them a more vivid understanding of how their ancestors lived and worshipped.

“When we read all of these texts about how the oils and the lamps worked, they don’t really make a lot of sense until you can picture that they are actually lighting oil and wicks,” Medwed said. “We all picture candles but suddenly things became so much clearer. Then they’re like, wait a second, this stuff isn’t so far away from us at all.”

Traditionalists

According to Leviticus 24:2, the Children of Israel were commanded to bring “pure olive oil beaten for the light, to cause a lamp to burn continually.” Some scholars believe the oil was so refined that an equivalent wasn’t produced for 2,000 years.

Despite olive oil’s shortcomings in the classroom, Medwed said the kids made it clear that it would be their choice to use at home if candles weren’t an option because that was what the holiday called for.

“I was genuinely surprised by that. I figured they were going to choose the corn oil, because it looked the prettiest or coconut oil because it was the most exotic or even schmaltz,” he said. “But they really said ‘I want to be more traditional with it.’”

The beauty of olive oil

Perhaps the Maccabees would have used corn oil if they had the opportunity in 167 B.C.E. But perhaps not, because olive oil has properties that make it uniquely suited for combustion, according to Mark Jones, an expert on petroleum chemistry with the American Chemical Society. It has a large amount of fatty acids that are partially made up of hydrocarbons, and that composition allows olive oil to “burn really well and produce a good amount of heat,” Jones said.

“During combustion, the heat produced is required to keep the fire going and for vaporizing the next molecules to burn,” he said. But unlike another hydrocarbon-rich substance, natural gas, the other components of olive oil’s molecular structure keep it from burning too cleanly. Natural gas doesn’t emit much light when it burns (“It makes a lousy lamp,” explained Jones) but olive oil is just inefficient enough to be useful as a light source.

Would it take a miracle?

As for whether the story that inspired Hanukkah is scientifically possible, that depends on how you frame it. Hayley Simon, a United Kingdom science journal editor who holds a Ph.D. in archaeology and once wrote about olive oil’s role in Hanukkah, pointed to the laws of thermodynamic reactions or kinetics, which states that the speed at which a reaction happens over a period of time is set — the Maccabees’ oil simply couldn’t have burned longer than it was supposed to.

“I think it took a miracle,” she said. “That’s why it’s a story that’s passed its way down to today.”

But Jones pointed out that the story of Hanukkah doesn’t give us all the variables. For instance, we don’t know how long the wick in the Temple’s menorah was — longer wicks consume fuel faster than smaller ones, Jones said. We also don’t know the exact composition of the oil.

“I haven’t ever run experiments to determine whether it is possible to extend a day’s worth of oil to eight days,” he said. “My attempt to stretch the oil for eight days would begin with a small wick and a high temperature oil. I wouldn’t mess with any of that if I were omnipotent. I would just magically refill the oil.”

Related

The post 5th grade scientists conduct a Hanukkah experiment to answer a burning question appeared first on The Forward.