________________________________

Cristhian Bahena Rivera

“Bahena”: Look! = Bak! (Bach, bakh, etc. – Turkish)

Bāhén a = Scars (Chinese)

| Mike Nova’s Shared NewsLinks |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cristhian Bahena Rivera – Google Search | ||||

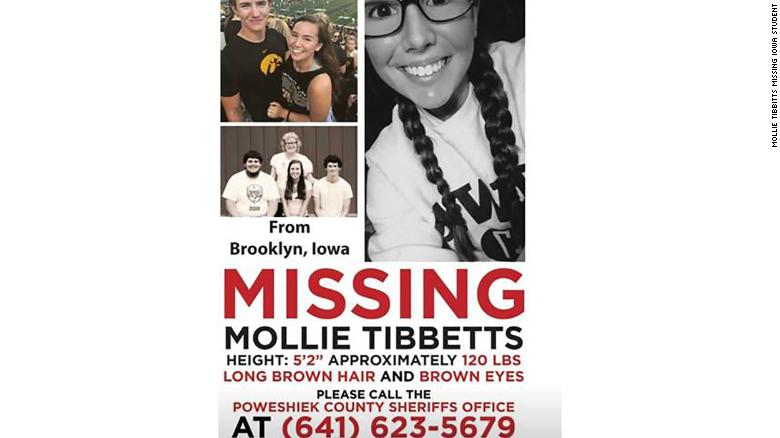

Mollie Tibbetts case: Man in country illegally charged with murder …<a href=”http://6abc.com” rel=”nofollow”>6abc.com</a>–3 hours ago

Iowa Division of Criminal Investigation Special Agent Rick Rahn said that Cristhian Bahena Rivera, 24, was charged with murder in the death of …

Mollie Tibbetts slain: Suspect Cristhian Bahena Rivera faces first …

The Gazette: Eastern Iowa Breaking News and Headlines–12 hours ago Read the criminal complaint, arrest warrant in the Mollie Tibbetts case<a href=”http://DesMoinesRegister.com” rel=”nofollow”>DesMoinesRegister.com</a>–12 hours ago

Authorities on Tuesday charged 24-year-old Cristhian Bahena Rivera with first-degree murder in the death of 20-year-old Mollie Tibbetts, the …

Watch Replay: Cristhian Bahena Rivera charged in Mollie Tibbetts …The Gazette: Eastern Iowa Breaking News and Headlines–14 hours ago

Update 6:17 p.m.: U.S. Sens. Chuck Grassley and Joni Ernst of Iowa today released the following statement regarding the announcement from …

Undocumented Immigrant Arrested in the Death of Missing University …Us Weekly–13 hours ago

Cristhian Bahena Rivera has been arrested and charged with murder in the first degree of missing University of Iowa student Mollie Tibbetts, …

READ MORE: Arrest warrant and affidavit for Cristhian Bahena Rivera<a href=”http://kwwl.com” rel=”nofollow”>kwwl.com</a>–13 hours ago

Cristhian Bahena Rivera is now in custody, after investigators say he admitted to interacting with Tibbetts while she was out on a jog on July 18 …

|

||||

| gov kim reynolds iowa – Google Search | ||||

|

||||

| gov kim reynolds iowa – Google Search | ||||

|

||||

| gov kim reynolds iowa – Google Search | ||||

|

||||

| 24-year-old man arrested, charged with murder of Mollie Tibbetts | ||||

MONTEZUMA, Iowa (KCRG-TV9) — A 24-year-old man in the U.S. illegally is charged with murder in the death of Mollie Tibbetts.

The 20-year-old University of Iowa student was last seen July 18 near Brooklyn, Iowa. During a news conference Tuesday, authorities announced a body found Tuesday morning in rural Poweshiek County is believed to be Mollie Tibbetts. They said Cristhian Rivera faces a first degree murder charge. Officials said Mollie Tibbetts was taken while jogging. They said surveillance cameras showed Rivera’s vehicle following Tibbetts the night she disappeared. Police said when they interviewed Rivera, he confessed to the killing, and later led them to her body. They said Rivera had left her body in a cornfield in rural Poweshiek County, near Guernsey. The Division of Criminal Investigation said Rivera has been living in Poweshiek County illegally between 4 and 7 years. CLICK HERE to view a complete timeline regarding the search for Tibbetts. Gov. Kim Reynolds has issued a statement on Mollie Tibbetts: “Today, our state woke up to heart-wrenching news. As a mother, I can’t imagine the sorrow felt by the Tibbetts family. We are all suffering over the death of Mollie, knowing that it could have been our own daughter, sister or friend. “I spoke with Mollie’s family and passed on the heartfelt condolences of a grieving state. I shared with them my hope that they can find comfort knowing that God does not leave us to suffer alone. Even in our darkest moments, He will comfort and heal our broken hearts. “I want to recognize and thank our local, state and federal law enforcement community for their coordinated and tireless efforts to find Mollie. “Over the past month, thousands of Iowans searched and prayed for Mollie’s safe return. Now, we are called to come together once again to lift up a grieving family. The search for Mollie is over, but the demand for justice has just begun. “As Iowans, we are heartbroken, and we are angry. We are angry that a broken immigration system allowed a predator like this to live in our community, and we will do all we can bring justice to Mollie’s killer.” _____ The University of Iowa has also released a statement: “We are deeply saddened that we’ve lost a member of the University of Iowa community. Our thoughts are with Mollie Tibbetts’ family, friends, and classmates. Losing a fellow student and member of our Hawkeye family is difficult. President Harreld and I share in your grief and encourage you to reach out if you are in need of support. A list of resources can be found on the university’s safety and support website (<a href=”http://www.uiowa.edu/homepage/safety-and-support” rel=”nofollow”>http://www.uiowa.edu/homepage/safety-and-support</a>) or by calling one of these offices: • University Counseling Services (319-335-7294) • Student Care and Assistance (319-335-1162) • UI Employee Assistance Program (319-335-2085) _____ Fred Hubbell, Democratic nominee for Iowa governor, released the following statement: “This is truly heartbreaking. For Mollie’s parents, her family and friends, any words today will be of little comfort. As a parent and grandparent your worst nightmare is losing your child. I know this must be an unimaginable loss. Please know our family and Iowans everywhere share your grief and are united in pursuit of justice. I want to commend our law enforcement officials who worked around the clock to investigate this crime. In this state, if you break the law, you will face the consequences.” |

||||

| mollie tibbetts – Google Search | ||||

24-year-old man arrested, charged with murder of Mollie TibbettsKCRG–8 hours ago

MONTEZUMA, Iowa (KCRG-TV9) — A 24-year-old man in the U.S. illegally is charged with murder in the death of Mollie Tibbetts.

Watch Replay: Cristhian Bahena Rivera charged in Mollie Tibbetts …

The Gazette: Eastern Iowa Breaking News and Headlines–13 hours ago Gov. Reynolds issues heartfelt statement on Mollie Tibbetts

<a href=”http://kwwl.com” rel=”nofollow”>kwwl.com</a>–12 hours ago |

||||

| Mollie Tibbetts case: Man leads police to body, faces murder charge | ||||

While authorities have yet to confirm the body is Tibbetts, they arrested Cristhian Bahena Rivera, 24, on first-degree murder charges.

The discovery dashed the hopes of family and friends who had scoured Poweshiek and nearby counties as rewards grew to nearly $400,000. Tibbetts, officials said, is believed to have been abducted on July 18 as she went out for an evening jog. Rivera, who’s an undocumented immigrant, told them Monday that he saw and pursued her, getting out of his car and running beside Tibbetts. She warned him she would call police, officials told reporters Tuesday. The suspect, who said he blacked out at some point, led authorities to the field Tuesday morning, they said. A body, dressed in Tibbetts’ clothing, was covered in corn leaves.

It is unclear why Rivera killed Tibbetts, said Rick Rahn, special agent in charge at the Iowa Division of Criminal Investigation.

“I can’t really speak to you about the motive,” Rahn said. “I can just tell you it seems that he followed her and seemed to be drawn to her on that particular day and for whatever reason he chose to abduct her.” An autopsy to determine when and how the woman died is planned for Wednesday. Authorities had been looking for Tibbetts about a month when they found home surveillance video that showed a car following a woman running. After watching it for hours, investigators found clues that led them to Rivera. He didn’t resist when authorities tried to detain him, Rahn said. The suspect is an undocumented immigrant who authorities believe has been in the area for four to seven years, Rahn said. Charges were filed in district court in Poweshiek County and bail was set at $1 million. If convicted Rivera could get life in prison without parole. Iowa does not have the death penalty. President Donald Trump referred to the case while speaking at a rally in Charleston, West Virginia. “You heard about today with the illegal alien coming in very sadly from Mexico. And you saw what happened to that incredible beautiful young woman. Should have never happened. Illegally in our country,” he said. “We’ve had a huge impact but the laws are so bad, the immigration laws are such a disgrace. We’re getting it changed but we have to get more Republicans.” Police: Tibbetts told suspect she would call copsAuthorities said the suspect followed Tibbetts on July 18, the video recorded by a home surveillance system shows. Extensive and lengthy searchTibbetts was on July 18 in the small community of Brooklyn, Iowa, about an hour east of Des Moines, according to the Poweshiek County Sheriff’s Office. Before she went missing, Tibbetts’ brother dropped her off at her boyfriend’s house so she could dog-sit, HLN reported. Her family reported her missing after she did not show up for work the next day.

The poster distributed asking for information about Mollie Tibbitts’ disappearance.

Investigators launched an extensive search for Tibbetts across the area, including in ponds, fields and from the air. CNN’s Dave Alsup, Sheena Jones, Chris Boyette, Kevin Liptak, Noah Gray, Cameron Markham and Kara Devlin contributed to this report. |

||||

| Mollie Tibbetts, missing Iowa student, found dead, her father says – Fox News | ||||

|

||||

| McCarthyism and the Second Red Scare | ||||

Page of

PRINTED FROM the OXFORD RESEARCH ENCYCLOPEDIA, AMERICAN HISTORY (<a href=”http://americanhistory.oxfordre.com” rel=”nofollow”>americanhistory.oxfordre.com</a>). (c) Oxford University Press USA, 2016. All Rights Reserved. Personal use only; commercial use is strictly prohibited (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

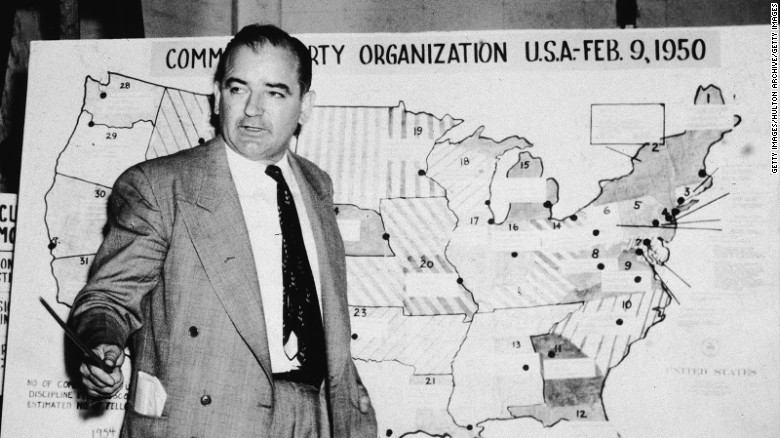

date: 21 August 2018 Summary and Keywords

The second Red Scare refers to the fear of communism that permeated American politics, culture, and society from the late 1940s through the 1950s, during the opening phases of the Cold War with the Soviet Union. This episode of political repression lasted longer and was more pervasive than the Red Scare that followed the Bolshevik Revolution and World War I. Popularly known as “McCarthyism” after Senator Joseph McCarthy (R-Wisconsin), who made himself famous in 1950 by claiming that large numbers of Communists had infiltrated the U.S. State Department, the second Red Scare predated and outlasted McCarthy, and its machinery far exceeded the reach of a single maverick politician. Nonetheless, “McCarthyism” became the label for the tactic of undermining political opponents by making unsubstantiated attacks on their loyalty to the United States.

The initial infrastructure for waging war on domestic communism was built during the first Red Scare, with the creation of an antiradicalism division within the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and the emergence of a network of private “patriotic” organizations. With capitalism’s crisis during the Great Depression, the Communist Party grew in numbers and influence, and President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal program expanded the federal government’s role in providing economic security. The anticommunist network expanded as well, most notably with the 1938 formation of the Special House Committee to Investigate Un-American Activities, which in 1945 became the permanent House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). Other key congressional investigation committees were the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee and McCarthy’s Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations. Members of these committees and their staff cooperated with the FBI to identify and pursue alleged subversives. The federal employee loyalty program, formalized in 1947 by President Harry Truman in response to right-wing allegations that his administration harbored Communist spies, soon was imitated by local and state governments as well as private employers. As the Soviets’ development of nuclear capability, a series of espionage cases, and the Korean War enhanced the credibility of anticommunists, the Red Scare metastasized from the arena of government employment into labor unions, higher education, the professions, the media, and party politics at all levels. The second Red Scare did not involve pogroms or gulags, but the fear of unemployment was a powerful tool for stifling criticism of the status quo, whether in economic policy or social relations. Ostensibly seeking to protect democracy by eliminating communism from American life, anticommunist crusaders ironically undermined democracy by suppressing the expression of dissent. Debates over the second Red Scare remain lively because they resonate with ongoing struggles to reconcile Americans’ desires for security and liberty. Keywords: anticommunism, communism, Martin Dies, Federal Bureau of Investigation, federal loyalty program, J. Edgar Hoover, House Un-American Activities Committee, Joseph McCarthy, political repression, Red Scare

The second Red Scare refers to the anticommunist fervor that permeated American politics, society, and culture from the late 1940s through the 1950s, during the opening phases of the Cold War with the Soviet Union. This episode lasted longer and was more pervasive than the first Red Scare, which followed World War I and the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917. Popularly known as “McCarthyism” after Senator Joseph McCarthy (R-Wisconsin), who made himself famous in 1950 by claiming that large numbers of Communists had infiltrated the U.S. State Department, the second Red Scare in fact predated and outlasted McCarthy, and its machinery far exceeded the reach of a single politician. “McCarthyism” remains an apt label for the demagogic tactic of undermining political opponents by making unsubstantiated attacks on their loyalty to the United States. But that term is too narrow to capture the complex origins, diverse manifestations, and sprawling cast of characters involved in the multidimensional conflict that was the second Red Scare. Defining the American Communist Party as a serious threat to national security, government and nongovernment actors at national, state, and local levels developed a range of mechanisms for identifying and punishing Communists and their alleged sympathizers. For two people, Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, espionage charges resulted in execution. Many thousands of Americans faced congressional committee hearings, FBI investigations, loyalty tests, and sedition laws; negative judgements in those arenas brought consequences ranging from imprisonment to deportation, loss of passport, or, most commonly, long-term unemployment.

Interpretations of the second Red Scare have ranged between two poles, one emphasizing the threat posed to national security by the Communist Party and the other emphasizing the threat to democracy posed by political repression. In the 1990s, newly accessible Soviet and U.S. intelligence sources revealed that more than three hundred American Communists—some Manhattan Project technicians and other government employees among them—indeed did pass information to the Soviets, chiefly during World War II. Scholars disagree about whether all these people understood themselves to be engaged in espionage and about how much damage they did to national security, but it is clear that the threat of espionage was real. So too, however, was repression in the name of catching spies. The second Red Scare remains a hotly debated topic because Americans continue to differ on the optimal balance between security and liberty and how to achieve it. Anticommunism has taken especially virulent forms in the United States because of distinctive features of its political tradition. As citizens of a relatively young and diverse republic, Americans historically have been fearful of “enemies within” and have drawn on their oft-noted predilection for voluntary associations to patrol for subversives. This popular predisposition in turn has been easier for powerful interests to exploit in the American context because of the absence of a parliamentary system (which elsewhere produced a larger number of political parties as well as stronger party discipline) and of a strong civil service bureaucracy. Great Britain, a U.S. ally in the Cold War, did not experience a comparable Red Scare even though it too struggled against espionage.1

Explaining American anticommunism requires an assessment of American communism. The 19th-century writings of Karl Marx gave birth to an international socialist movement that denounced capitalism for exploiting the working class. Some socialists pursued reform through existing political systems while others advocated revolution. Russia’s Bolshevik Revolution in 1917 encouraged those in the latter camp. The American Communist Party (CPUSA), established in 1919, belonged to the Moscow-based Comintern, which provided funding and issued directives, ostensibly to encourage Communist revolutions around the world but in practice to support Soviet foreign-policy objectives. The CPUSA remained small and factionalized until the international economic crisis and the rise of European fascism in the 1930s increased its appeal. During the Great Depression, “the heyday of American communism,” party members won admiration from the broader Left for their effective organizing on behalf of industrial and agricultural workers and for their bold denunciation of lynching, poll taxes, and other instruments of white supremacy. In 1935, party leaders adopted a strategy of cooperating with noncommunists in a “Popular Front against fascism.” Party members joined or organized groups that criticized Adolf Hitler’s policies and supported the Spanish resistance to General Francisco Franco. They also drew connections between fascism abroad and events at home, from the violent suppression of striking miners, textile workers, and farmworkers, to the unfair trial of the “Scottsboro boys” (nine African American teenagers from Alabama accused of raping two white women), to prohibitions on married women’s employment. Not always aware of the participation of Communists, diverse activists worked through hundreds of Popular Front organizations on behalf of labor, racial and religious minorities, and civil liberties. The CPUSA itself grew to about 75,000 members in 1938; many times that number participated in Popular Front causes.2 Because rank-and-file members often kept their party affiliation secret as they attempted to influence Popular Front groups, the term “front organization” came to connote duplicity rather than solidarity.

The Popular Front period ended abruptly in August 1939, when the Soviet and German leaders signed a nonaggression pact. Overnight the CPUSA abandoned its fight against fascism to argue for “peace” and against U.S. intervention in Europe. Exposing the American party leadership’s subservience to Moscow, this shift alienated many party members as well as the noncommunist leftists and liberals who had been willing to cooperate toward shared objectives. In June 1941, Hitler broke the pact by invading the Soviet Union, and the Soviets became American allies. Reversing course again, American Communists enthusiastically supported the Allied war effort, and the party’s general secretary, Earl Browder, adopted a reformist rather than revolutionary program. With Hitler’s defeat, however, the fragile Soviet-American alliance dissolved; U.S. use of atomic weapons in Japan and Soviet expansionism in Eastern Europe inaugurated the long Cold War between the two powers. In 1945 William Z. Foster replaced Browder at the head of the American party, which now harshly denounced capitalism and President Harry Truman’s foreign policy. Riven by internal disputes and increasingly under attack from anticommunists, the CPUSA became more isolated. Its numbers had dwindled to below 10,000 by 1956, when the Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev officially acknowledged what many American Communists had refused to believe: that Stalin had been responsible for the death of millions in forced labor camps and in executions of political rivals. After these revelations, the CPUSA faded into insignificance.3 As the historian Ellen Schrecker has observed, American Communists were neither devils nor saints. The party’s secretiveness, its authoritarian internal structure, and the loyalty of its leaders to the Kremlin were fundamental flaws that help explain why and how it was demonized. On the other hand, most American Communists were idealists attracted by the party’s militance against various forms of social injustice. The party was a dynamic part of the broader Left that in the 1930s and 1940s advanced the causes of labor, minority rights, and feminism.4

Anticommunists were less unified than their adversary; diverse constituencies mobilized against communism at different moments.

During the violent industrial conflicts of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, employers and employer associations frequently avoided acknowledging workers’ grievances, by charging that foreign-born radicals were fomenting revolution. Employers often enlisted local law officers and private detectives in their efforts to quell labor militancy, which they cast as unpatriotic. The correlation between labor unrest and anticommunist zeal was enduring. The first major Red Scare emerged during the postwar strike wave of 1919 and produced the initial infrastructure for waging war on domestic communism. Diverse strikes across the nation coincided with a series of mail bombings by anarchists. Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer charged that these events were evidence of a revolutionary conspiracy. Palmer directed the young J. Edgar Hoover, head of the General Intelligence Division of the Bureau of Investigation (later renamed the Federal Bureau of Investigation, or FBI), to arrest radicals and their associates and to deport the foreign born among them. The ensuing raids and surveillance activities violated civil liberties, and in 1924 the bureau was reined in. But Hoover became FBI director, a position he would hold until his death in 1972. Intensely anticommunist, and prone to associating any challenge to the economic or social status quo with communism, Hoover would be a key player in the second Red Scare. Other early participants in the anticommunist network were Red squads on metropolitan police forces, patriotic societies and veterans’ groups, and employer associations such as the National Association of Manufacturers and U.S. Chamber of Commerce.5 After the wartime federal sedition and espionage laws expired, and after the FBI was curbed, state and local officials took primary responsibility for fighting communism. By 1921 thirty-five states had passed sedition or criminal syndicalism laws (the latter directed chiefly at labor organizations and vaguely defined to prohibit sabotage or other crimes committed in the name of political reform).6 Through the 1920s and into the 1930s, anticommunists mobilized in local battles with labor militants; for example, in steel, textiles, and agriculture and among longshoremen. The limitations of the American Federation of Labor (AFL) in organizing mass-production industries led to the emergence of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), which organized workers regardless of craft into industry-wide unions such as the United Automobile Workers. Encouraged by the National Labor Relations Act of 1935, the CIO pioneered aggressive tactics such as the sit-down strike and further distinguished itself from the AFL with its organizing efforts among women and racial minorities. These positions attracted Communists to the CIO’s service, leading anti-union forces to charge that the CIO was a tool of Communist revolutionaries (a charge that the AFL echoed). Charges of communism were especially common in response to labor protests by African Americans in the South and by Mexican Americans in the West.7 Education was another anticommunist concern during the interwar period. Groups such as the American Legion pressured school boards to drop “un-American” books from the curriculum. By 1936, twenty-one states required loyalty oaths for teachers. School boards and state legislatures investigated allegations of subversion among teachers and college professors.8 Also in these interwar years, organized Catholics joined the campaign against “godless” communism. Throughout this period, the federal role in fighting communism consisted mainly of using immigration law to keep foreign-born radicals out of the country, but the FBI continued to monitor the activities of Communists and their alleged sympathizers.9 The political and legal foundations of the second Red Scare thus were under construction well before the Cold War began. In Congress, a conservative coalition of Republicans and southern Democrats had crystallized by 1938. Congressional conservatives disliked many New Deal policies—from public works to consumer protection to, above all, labor rights—and they frequently charged that the administering agencies were influenced by Communists. In 1938 the House authorized a Special Committee to Investigate Un-American Activities, headed by Martin Dies, a Texas Democrat. Dies was known as a leading opponent of the National Labor Relations Act of 1935, the CIO, and the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938. The Dies Committee devoted most of its attention to alleged Communists in the labor and consumer movements and in New Deal agencies such as the Works Progress Administration (WPA). For his chief investigator, Dies hired J. B. Matthews, a self-proclaimed former fellow traveler of the Communist Party who later would serve on Senator McCarthy’s staff. Matthews forged a career path for ex-leftists whose perceived expertise was valuable to congressional committees, the FBI, and anti–New Deal media magnates such as William Randolph Hearst. In one early salvo against the Roosevelt administration, Dies Committee members called for the impeachment of Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins because she refused to deport the Communist labor leader Harry Bridges; Perkins claimed (correctly) that she did not have the legal authority to deport him.10 The Bridges controversy and the Stalin-Hitler Pact of August 1939 gave impetus to the passage of Alien Registration Act of 1940, known as the Smith Act for its sponsor Representative Howard Smith, the Virginia Democrat whose own House committee was investigating alleged Communist influence on the National Labor Relations Board. The Smith Act made it illegal to advocate overthrow of the government, effectively criminalizing membership in the Communist Party, and allowed deportation of aliens who ever had belonged to a seditious organization. Congressional conservatives also engineered passage of the 1939 Hatch Act, which prohibited federal employees from engaging in political campaigning and from belonging to any group that advocated “the overthrow of the existing constitutional form of government.”11 The law’s passage was driven by the first provision, which responded to allegations that Democratic politicians were using WPA jobs for campaign purposes. It was the Hatch Act’s other provision, however, that created a vital mechanism of the second Red Scare.

To enforce the Hatch Act, the U.S. attorney general’s office generated a list of subversive organizations, and employing agencies requested background checks from the FBI, which checked its own files as well as those of the Dies Committee. FBI agents interviewed government employees who admitted having or were alleged to have associations with any listed group. Congressional conservatives continued accusing the Roosevelt administration of harboring Communists, even after Adolf Hitler’s invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941 put the Soviets in the Allied camp. Martin Dies charged that the wartime Office of Price Administration, the Federal Communications Commission, and other regulatory agencies were run by Communists and “crackpot, radical bureaucrats.” The Civil Service Commission (CSC) created a loyalty board, which reviewed employees named by Dies. When most of those employees were retained, the Dies Committee charged that CSC examiners themselves had subversive tendencies. In 1943 the Dies Committee subpoenaed hundreds of CSC case files in an effort to prove that charge.12

The Roosevelt administration and its supporters dismissed Dies and his ilk as fanatics, but in 1946 accusations that Communists had infiltrated government agencies began to get traction. Public anxiety about postwar inflation and another strike wave was intensified by Soviet expansionism in Eastern Europe and by Russian defector Igor Gouzenko’s exposure of a Canadian spy ring. Highlighting the “Communists in government” issue helped the Republican Party make sweeping gains in the 1946 midterm elections, leading President Harry Truman to formalize and expand the makeshift wartime loyalty program. The second Red Scare derived its momentum from fears that Communist spies in powerful government positions were manipulating U.S. policy to Soviet advantage. The federal employee loyalty program that Truman authorized in an attempt to neutralize right-wing accusations became instead a key force in sustaining and spreading “the great fear.” Truman’s March 1947 Executive Order 9835 directed executive departments to create loyalty boards to evaluate derogatory information about employees or job applicants. Employees for whom “reasonable grounds for belief in disloyalty” could be established were to be dismissed. To assist in implementing the loyalty program, the Attorney General’s List of Subversive Organizations (AGLOSO) was made public for the first time. Millions of federal employees filled out loyalty forms swearing they did not belong to any subversive organization and explaining any association they might have with a designated group. Agency loyalty boards requested name checks and sometimes full field investigations by the FBI, which promptly hired 7,000 additional agents. Among the many sources that the FBI checked were the ever-expanding files of the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), which in 1945 had replaced the Dies Committee.13 During the program’s peak between 1947 and 1956, more than five million federal workers underwent loyalty screening, resulting in an estimated 2,700 dismissals and 12,000 resignations. Those numbers exclude job applicants who were rejected on loyalty grounds. More importantly, those numbers exclude the tens of thousands of civil servants who eventually were cleared after one or more rounds of investigation, which could include replying to written interrogatories, hearings, appeals, and months of waiting, sometimes without pay, for a decision. The program’s oft-noted flaws included the ambiguous definition of “derogatory” information and the anonymity of informants who provided it, the reliance on an arbitrary and changing list of subversive organizations, and a double-jeopardy problem for employees for whom a move from one government job to another triggered reinvestigation on the same grounds. Those grounds usually consisted of a list of individually minor associations that dated back to the 1930s. Because loyalty standards became more restrictive over time, employees who did not change jobs too faced reinvestigation, even in the absence of new allegations against them.14 Loyalty standards tightened as the political terrain shifted. During the summer of 1948, the ex-Communists Elizabeth Bentley and Whittaker Chambers testified before HUAC that in the 1930s and early 1940s they had managed Washington spy rings that included dozens of government officials, including the former State Department aide Alger Hiss. A Harvard Law School graduate who had been involved in the formation of the United Nations, Hiss vigorously denied the allegations, and Truman officials defended him. Hiss was convicted of perjury in 1950. Meanwhile, the Soviets developed nuclear capability sooner than expected, Communists took control in China, Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were convicted, and North Korea invaded South Korea. This combination of events increased the Truman administration’s vulnerability to partisan attacks. Senator McCarthy claimed to explain those events by alleging that Communists had infiltrated the U.S. State Department. Congress then in effect broadened the loyalty program by passing Public Law 733, which empowered heads of sensitive agencies to dismiss an employee on security grounds. An employee deemed loyal could nonetheless be labeled a security risk because of personal circumstances (alcoholism, homosexuality, a Communist relative) that were perceived to create vulnerability to coercion. A purge of homosexuals from the State Department and other agencies ensued. Over Truman’s veto, in 1950 Congress also passed the McCarran Internal Security Act, which required Communist organizations to register with the U.S. attorney general and created the Subversive Activities Control Board. The new Senate Internal Security Subcommittee (SISS), headed by Patrick McCarran (D-Nevada), was soon vying with HUAC for headlines about the battle against Communists on the home front. After McCarthy claimed the loyalty program was clearing too-many employees on appeal, Truman’s Executive Order 10241 of April 1951 lowered the standard of evidence required for dismissal. That same month the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the loyalty program’s constitutionality, a reminder that all three branches of government built the scaffolding for the Red Scare. The standards changed again in April 1953 with Eisenhower’s Executive Order 10450, which extended the security risk standard to every civil service job, imposed more-stringent “morals” tests, and eliminated defendants’ right to a hearing. It was not unusual for a career civil servant to be investigated under the Hatch Act during World War II and then again after each executive order. Of the more than 9,300 employees who were cleared after full investigation under the 1947 standard, for example, at least 2,756 saw their cases reopened under the 1951 standard. Employees who had been cleared never knew when their case might be reopened. Even after the loyalty program was curbed in the late 1950s, the FBI continued to keep tabs on former loyalty defendants. Loyalty investigations often did lasting damage to employees’ economic security, mental and physical health, personal relationships, and civic participation.15 Because most of those dismissed under the loyalty program were low-level employees, the program’s policy impact, at least outside the State Department’s jurisdiction, has sometimes been underestimated. Unlike dismissals, investigations occurred across the ranks, so all civil servants felt the pressure. Case files declassified in the early 21st century indicate that loyalty investigations truncated or redirected the careers of many high-ranking civil servants, who typically kept secret the fact that they had been investigated. Many of them were noncommunist but left-leaning New Dealers who advocated measures designed to expand democracy by regulating the economy and reducing social inequalities. Their fields of expertise included labor and civil rights, consumer protection, welfare, national health insurance, public power, and public housing; their marginalization by charges of disloyalty impeded reform in these areas and narrowed the scope of political discourse more generally. Through the federal loyalty program, conservative anticommunists exploited public fears of espionage to block policy initiatives that impinged on private-sector prerogatives.16

The loyalty program for federal employees was accompanied by similar programs focused on port security and industrial security. Private employees on government contracts also faced screening, and state and local governments soon imitated the federal programs. Public universities revived mandatory loyalty oaths. In 1953, Americans employed by international organizations such as the United Nations became subject to Civil Service Commission loyalty screening, over protests that such screening violated the sovereignty of the international organizations. One researcher estimated in 1958 that approximately 20 percent of the U.S. labor force faced some form of loyalty test.17 Although espionage trials and congressional hearings were the most-sensational manifestations of McCarthyism, loyalty tests for employment directly affected many more people.

Beyond the realms of government, industry, and transport, anticommunists trained their sights on those arenas where they deemed the potential for ideological subversion to be high, including education and the media. The entertainment industry was an especially attractive target for congressional investigating committees seeking to generate sensational headlines. The House Un-American Activities Committee’s (HUAC’s) 1947 investigation of Communist influence in Hollywood was an early example. Building on an earlier investigation by California’s Tenney Committee, HUAC subpoenaed a long list of players in the film industry. Many of them, including the actor Ronald Reagan, cooperated with HUAC by naming people they believed to be Communists. By contrast, a group that became known as the “Hollywood Ten” invoked their First Amendment right to freedom of association and challenged the committee’s right to ask about their political views. Eventually, after the Supreme Court refused to hear their case, the ten directors and screenwriters spent six months in prison. For more than a decade beyond that, they were blacklisted by Hollywood employers.18 Later, “unfriendly witnesses” declined to answer questions posed by the investigating committee, by citing their Fifth Amendment right not to incriminate themselves. This tactic provided legal protection from prison, but “taking the Fifth” was widely interpreted as tantamount to an admission of guilt, and many employers refused to employ anyone who had so pleaded. Another limitation of the Fifth Amendment strategy was that it did not waive witnesses’ obligation to answer questions about others. Congressional committees pressed witnesses to “name names” of people they knew to be Communists as evidence that they were not sympathetic, or were no longer sympathetic, to communism. Whether or not they answered questions about their own politics, witnesses’ moral dilemma over whether to identify others as Communists became one of the most familiar, and to critics most infamous, of McCarthyism’s dramatic episodes.19 The entertainment industry blacklist did not end with HUAC’s investigation of Hollywood. As countersubversives issued a steady flow of accusations, the cloud of suspicion expanded. In 1950, the authors of the anticommunist newsletter Counterattack, who included several former FBI agents, released a booklet called Red Channels: The Report of Communist Influence in Radio and Television. It listed 151 writers, composers, producers, and performers and included a long list of allegedly subversive associations for each person. The booklet was riddled with factual errors. Some of those listed were or had been Communists, but others had not. In any case, they and those on similar lists found it nearly impossible to get work in their fields; some could get hired only by working under another name. The fear of unemployment produced many ripple effects beyond those felt at the individual level. The second Red Scare curtailed Americans’ willingness to join voluntary organizations. Groups were added to the U.S. attorney general’s list over time, and zealous anticommunists frequently charged that one group or another should be added to the list, including such mainstream, reformist organizations as the National Council of Jewish Women, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and the American Association of University Women. Very few of the roughly 280 organizations on the official list engaged in illegal activity.20 Still, association with any listed group could become a bar to employment, and also potentially a justification for exclusion from public housing and veterans’ benefits. Rather than take chances, many people stopped belonging to organizations. Being known as a “joiner” of causes acquired the connotation of being an easy mark for Communists, and defense attorneys encouraged their clients to present themselves as allergic to such activity.21 Civic groups lost membership, and many Americans hesitated to sign petitions or engage in any activism that might possibly be construed as controversial. The second Red Scare also reshaped the American labor movement. By the end of World War II, a dozen Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) unions had Communist party members among their officers. Top CIO leaders tolerated Communists at first, valuing their dedication and hoping to avoid internal division and external attack. In 1947, however, congressional conservatives overrode President Harry Truman’s veto and passed the Taft-Hartley Act, which, among other things, required all union officers to swear that they were not Communists or else to face loss of support from the National Labor Relations Board. Many trade union members, especially Catholics, were intensely anticommunist and stepped up their effort to oust Communists from their leadership. In 1948 the Communist Party made the position of its members in the labor movement more difficult by supporting the Progressive Party candidate Henry Wallace rather than President Truman. Liberal anticommunists in the American Federation of Labor (AFL) and Americans for Democratic Action joined conservatives in attacking the CIO’s leftist-led unions, which the CIO finally expelled in 1949 and 1950. The expulsions embittered many workers and labor allies, and they did not prevent right-wing groups from associating trade unionism with communism.22

Many factors combined to weaken McCarthyism’s power in the latter half of the 1950s. With a Republican in the White House as a result of the 1952 election, the partisan motivation for attacking the administration as soft on communism diminished. Opportunists such as Senator McCarthy made increasingly outrageous charges to remain in the spotlight, straining the patience of President Dwight Eisenhower and other Republican leaders such as Robert Taft of Ohio. In 1953 McCarthy became chair of the Senate Committee on Government Operations, and he used its Subcommittee on Investigations to hold hearings on alleged Communist influence in the State Department’s Voice of America and overseas library programs. The book burnings that resulted from the latter investigation, and the forced resignation of the committee’s research director, J. B. Matthews, after he claimed that the Protestant clergy at large had Communist sympathies, increased public criticism of McCarthy. Newspaper and television journalists began featuring the cases of government employees unfairly dismissed as loyalty or security risks, and various foundations and congressional committees undertook studies that gave further impetus to demands for reforming the loyalty program. McCarthy responded to his critics—from Edward Murrow of the See It Now television program to his fellow legislators—by accusing them of Communist sympathies. His conduct and that of his subordinate Roy Cohn in pressing unsubstantiated charges of disloyalty in the U.S. Army led to televised hearings beginning in April 1954, which gave viewers an extended opportunity to see McCarthy in action. McCarthy’s popularity declined markedly as a result. In December the Senate censured McCarthy. A few months later, the FBI informant Harvey Matusow recanted, claiming that McCarthy and others had encouraged him to give false information and that he knew other ex-Communist witnesses, such as Elizabeth Bentley and Louis Budenz, to have done the same.

Changes in the composition of the Supreme Court also dampened the fervor of the anticommunist crusade. Four justices were replaced between 1953 and 1957, and under Chief Justice Earl Warren the court issued several rulings that limited the mechanisms designed to identify and punish Communists. In 1955 and 1956, the court held that the federal loyalty program could apply only to employees in sensitive positions. In 1959, the court struck down the program’s reliance on anonymous informants, giving defendants the right to confront their accusers.23 Meanwhile, on a single day in 1957, the court limited the powers of congressional investigating committees, restricted the enforcement of the Smith Act on First Amendment grounds and overturned the convictions of fourteen members of the Communist Party of California, and reinstated John Stewart Service to the State Department, which had dismissed him on loyalty grounds in 1951. Members of the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee (SISS) accused the Supreme Court of weakening the nation’s defenses against communism, and FBI director J. Edgar Hoover angrily labeled June 17, 1957, “Red Monday.” Civil libertarians, by contrast, welcomed the rulings but regretted that they were based narrowly on procedural questions rather than on broad principles.24 With McCarthy’s disgrace and the Supreme Court’s restrictions on its machinery, the second Red Scare lost much of its power. One government personnel director opined in 1962 that 90 percent of the people who had been dismissed on loyalty grounds in the early 1950s would have had no difficulty under the same circumstances a decade later. Even so, the damage lasted a long time. The applicant pool for civil service jobs contracted sharply and did not soon recover. Former loyalty defendants, even those who had been cleared, lived the rest of their lives in fear that the old accusations would resurface. Sometimes they did; during President Lyndon Johnson’s administration, many talented people were passed over for appointments, not because hiring officials doubted their loyalty, but because appointing them risked politically expensive controversy.25 The loyalty programs and blacklists wound down, but anticommunism remained a potent force through the 1960s and beyond. After court rulings limited the usefulness of state and national sedition laws against members of the Communist Party, FBI director Hoover launched the secret COINTEL program to monitor and disrupt Communists and others he deemed subversive. Targets soon included participants in the civil rights, anti–Vietnam War, and feminist movements.26 Well into the 1960s, local Red Scares waxed and waned in tandem with challenges to the local status quo, above all in southern contexts where white supremacists battled civil rights activists. Segregationists such as Alabama governor George Wallace and Mississippi senator James Eastland—who not incidentally chaired SISS from 1955 to 1977—routinely linked race reform to communism and charged that “outside agitators” bent on subverting southern traditions were behind demands for integration and black voting rights.27

Scholarship on the second Red Scare has emerged in waves, responding to the availability of new sources, changing historical methodologies, and shifting political contexts.28

Initial debates centered on assessing the causes of, or motivations behind, the anticommunist furor. Richard Hofstadter’s influential interpretation explained McCarthy’s popularity in psychological terms as a manifestation of the “status anxiety” of those who resented the changes associated with a more modern, pluralistic, secular society. Treating McCarthyism as an episode of mass irrationality, Hofstadter argued that its “real function” was “not anything so simply rational as to turn up spies . . . but to discharge resentments and frustrations, to punish, to satisfy enmities whose roots lay elsewhere than in the Communist issue itself.”29 Subsequent scholarship demonstrated that Hofstadter’s view neglected the role of elites, from congressional conservatives to liberal anticommunists to the FBI, in orchestrating the second Red Scare. Some accounts emphasized the partisan pressures from Republicans and southern Democrats on the Truman administration.30 Others placed a larger share of the responsibility on Cold War liberalism itself. Some of these scholars wrote from a critical stance influenced by the Vietnam-era disillusionment of the New Left, while others applauded liberal anticommunism and focused on how McCarthy had discredited it.31 After the post-Watergate strengthening of the Freedom of Information Act made FBI records accessible, attention shifted to the repressive tactics of J. Edgar Hoover, who put citizens under illegal surveillance, leaked information to congressional conservatives, and stood by informants known to be unreliable.32 In depicting a top-down Red Scare orchestrated by elites, historians writing in the 1960s and 1970s were out of step with their discipline’s shift toward social history. That disjuncture was soon mitigated by an outpouring of studies of Communist activity at the grassroots, in diverse local contexts usually far removed from foreign affairs.33 The tenor of debate shifted again when the end of the Cold War made available new evidence from Soviet archives and U.S. intelligence sources such as the VENONA decrypts. That evidence indicated that scholars had underestimated the success of Soviet espionage in the United States as well as the extent of Soviet control over the American Communist Party. Alger Hiss, contrary to what most liberals had believed, and contrary to what he maintained until his death in 1996, was almost certainly guilty of espionage. A few hundred other Americans were secret Communist Party members and shared information with Soviet agents, chiefly during World War II.34 Some historians interpreted the new evidence to put anticommunism in a more sympathetic light and to criticize scholarship on the positive achievements of American Communists.35 Others concluded that the reality of espionage did not lessen the damage done in the name of anticommunism. The stakes of the debate rose after the September 11, 2001, attacks on the United States produced the Patriot Act, which rekindled ideological disagreement over the proper balance between national security and civil liberties; commentators who feared that the “war on terrorism” would be used to quell domestic dissent cited McCarthyism as the relevant historical precedent. The new evidence did not resolve scholarly differences, but it produced a more complicated, frequently less romantic view of the American Communist Party (CPUSA). The paradoxical lesson from several decades of scholarship is that the same organization that inspired democratic idealists in the pursuit of social justice also was secretive, authoritarian, and morally compromised by ties to the Stalin regime.36 The opening of government records also afforded a clearer view of the machinery of the second Red Scare, and that view has reinforced earlier judgements about its unjust and damaging aspects. In addition to new books on Hoover and the FBI, scholars have produced freshly documented studies of the Attorney General’s List of Subversive Organizations (AGLOSO), the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee (SISS), and leading anticommunists and their informants.37 Scholarship since the late 20th century has tried to transcend the old debates by turning to new approaches. Comparative studies have been useful in exploring the interaction between popular and elite forces in generating and sustaining anticommunism. Michael J. Heale’s analysis of Red Scares in three states identifies a common denominator in the role of political fundamentalists who feared the trend toward a “pluralistic order and a secular, bureaucratizing state.” But local power struggles shaped the timing and target of anticommunist furor. Detroit’s Red Scare erupted as the city’s manufacturing leaders tried to defend their class prerogatives from unions; in Boston, conflict between Catholics and Protestants fueled red-baiting, while Atlanta’s Red Scare became most virulent later, as civil rights activists threatened white supremacy. These and other local- and state-level studies demonstrate that the intensity of Red Scare politics was not a simple function of the strength of the Communist threat. Rather, Red Scares caught fire where rapid change threatened old regimes. Varying mixtures of elite and grassroots forces mobilized to defend local hierarchies, whether of class, religion, race, or gender.38International comparisons are bearing fruit too, not least by bringing into sharper relief distinctive aspects of state structure and political development that encouraged or restrained Red Scares.39 Attention to gender as a category of historical analysis has added another dimension to our understanding of the second Red Scare. The “containment” strategy for halting the spread of communism abroad had a domestic counterpart that prescribed rigid gender roles within the nuclear family. Domestic anticommunism was fueled by widespread anxiety about the perceived threats to American masculinity posed by totalitarianism, corporate hierarchy, and homosexuality. Congressional conservatives used charges of homosexuality—chiefly male homosexuality—in government agencies to serve their own political purposes. High-ranking women in government too were especially frequent targets of loyalty charges, as conservative anticommunists tapped popular hostility to powerful women to rally support for hunting subversives and blocking liberal policies.40 A related trend in the literature situates McCarthyism within a longer anticommunist tradition. In addition to looking at 19th-century antecedents, early-21st-century work explores the political and institutional continuities between the first and second Red Scares and also notes how conservatives’ deployment of anticommunism to fracture the Democratic Party’s electoral coalition along race and gender lines prefigured the New Right ascendancy under President Ronald Reagan.41 This longer-term view also has invited further attention to variations within anticommunism, yielding a more nuanced portrait of its diverse conservative, liberal, labor, and socialist camps.42 Even as they continue to debate the second Red Scare’s origins and sustaining mechanisms, scholars are paying more attention to its effects. Aided by newly accessible materials such as FBI files and the unpublished records of congressional investigating committees, historians are documenting in concrete detail how the fear of communism, and the fear of punishment for association with communism, affected specific individuals, organizations, professions, social movements, public policies, and government agencies.43 The drive to eliminate communism from all facets and arenas of American life engaged diverse players for many years, and scholars continue to catalogue its direct and indirect consequences.

In a useful 1988 survey of archival sources on McCarthyism, Ellen Schrecker suggests looking for evidence created by various categories of players: inquisitors, targets, legitimizers, defenders of targets, and observers.44 It is with regard to the first two categories, especially, that new sources have become accessible. FBI files on individuals and organizations are revealing both about the targets and the inquisitors; some frequently requested files are available online, and others can be obtained, with patience, through a Freedom of Information Act Request. Washington, DC–area branches of the National Archives hold records of surviving case files from the federal employee loyalty program (Record Group 478.2), the Subversive Activities Control Board (Record Group 220.6), the House Committee on Un-American Activities and its predecessor (Record Group 233.25.1, 233.25.2), the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee (Record Group 46.15), and the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations (Record Group 46.13). The rich papers of anticommunist investigator J. B. Matthews are at Duke University. The Roosevelt, Truman, and Eisenhower Presidential Libraries hold relevant collections on each administration’s handling of “the communist problem.” The Library of Congress holds the papers of Supreme Court justices Hugo Black and William O. Douglas and of Truman’s attorney general James McGranery, while the papers of the many U.S. and state legislators who were prominent among the accusers and the accused can be found in various archives in their home states. Records of the American Legion can be found at the State Historical Society of Wisconsin and Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

The Tamiment Library and Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives at New York University holds the papers of the prime target of the second Red Scare—the Communist Party USA—as well as many related collections. The Fund for the Republic studied McCarthyism and subsequently became a target; its papers are at the Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library at Princeton University. Also at Princeton are the papers of Paul Tillett Jr., a political scientist who in the 1960s collected but never published a wide range of data on McCarthyism, and American Civil Liberties Union papers. Because so many groups and individuals participated in the second Red Scare in one role or another, manuscript and oral-history collections in archives all over the country hold relevant material. Good examples include the State Historical Society of Wisconsin, which holds the records of the Americans for Democratic Action, Highlander Folk School, and United Packinghouse Workers Union, among many other pertinent collections; the National Lawyers’ Guild papers at the Bancroft Library, University of California at Berkeley; the papers of the Civil Rights Congress at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library; and labor movement records at the Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University, and the George Meany Memorial AFL-CIO Archives, University of Maryland. Among the many published memoirs of participants, see Owen Lattimore, Ordeal by Slander (1950); Whittaker Chambers, Witness (1952); Alger Hiss, In the Court of Public Opinion (1957); Peggy Dennis, Autobiography of an American Communist (1977); and John J. Abt, Advocate and Activist: Memoirs of an American Communist Lawyer (1993). Further Reading

Fried, Richard M. Nightmare in Red: The McCarthy Era in Perspective. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991.Find this resource:

Goldstein, Robert Justin. American Blacklist: The Attorney General’s List of Subversive Organizations. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2008.Find this resource: Griffith, Robert. The Politics of Fear: Joseph R. McCarthy and the Senate. 2d ed. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1987.Find this resource: Haynes, John Earl, and Harvey Klehr. Early Cold War Spies: The Espionage Trials That Shaped American Politics. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006.Find this resource: Heale, Michael J. McCarthy’s Americans: Red Scare Politics in State and Nation, 1935–1965. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1998.Find this resource: Johnson, David K. The Lavender Scare: The Cold War Persecution of Gays and Lesbians in the Federal Government. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004.Find this resource: Olmsted, Kathryn S. Red Spy Queen: A Biography of Elizabeth Bentley. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002.Find this resource: Oshinsky, David M. A Conspiracy So Immense: The World of Joe McCarthy. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.Find this resource: Schrecker, Ellen. Many Are the Crimes: McCarthyism in America. Boston: Little, Brown, 1998.Find this resource: Storrs, Landon R. Y. The Second Red Scare and the Unmaking of the New Deal Left. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2012.Find this resource: Theoharis, Athan G., and John Stuart Cox. The Boss: J. Edgar Hoover and the American Inquisition. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1988.Find this resource: Notes:

(1.) Joan Mahoney, “Civil Liberties in Britain during the Cold War: The Role of the Central Government,” American Journal of Legal History 33, no. 1 (1989), 53–100; Markku Ruotsila, British and American Anti-communism before the Cold War (New York: Routledge, 2001); and Michael J. Heale, “Beyond the ‘Age of McCarthy’: Anticommunism and the Historians,” in Melvyn Stokes, ed., The State of U.S. History (New York: Berg, 2002), 131–153.

(2.) On Communist Party membership, see Soviet and American Communist Parties, in Revelations from the Russian Archives, Library of Congress. For an introduction to the vast literature on the Communist Party, see Harvey Klehr, The Heyday of American Communism: The Depression Decade (New York: Basic Books, 1984); Robin D. G. Kelley, Hammer and Hoe: Alabama Communists during the Great Depression (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1990); Michael Denning, The Cultural Front: The Laboring of American Culture in the Twentieth Century (New York: Verso, 1997); and Kate Weigand, Red Feminism: American Communism and the Making of Women’s Liberation (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002).

(3.) Curt Gentry, J. Edgar Hoover: The Man and the Secrets (New York: W. W. Norton, 1991), 442; and Robert Conquest, The Great Terror: A Reassessment, 40th anniversary ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008).

(4.) Ellen Schrecker, Age of McCarthyism: A Brief History with Documents (Boston: Bedford, 1994), 3; see also Michael Kazin, “The Agony and Romance of the American Left,” American Historical Review 100, no. 5 (1995), 1488–1512. Since the opening of Soviet archives at the end of the Cold War, an outpouring of scholarship has elaborated on both sides of the paradox—on one hand, the American party’s complicity in espionage and with the Stalin regime, and on the other hand, its vital role in democratic social movements. For skepticism of this dualistic assessment of American communism, see John Earl Haynes and Harvey Klehr, In Denial: Historians, Communism & Espionage (San Francisco: Encounter Books, 2003), 134–139.

(5.) Chad Pearson, “Fighting the ‘Red Danger’: Employers and Anti-communism,” Athan Theoharis, “The FBI and the Politics of Anti-communism, 1920–1945,” and Michael J. Heale, “Citizens versus Outsiders: Anti-communism at State and Local Levels, 1921–1946,” all in Robert Goldstein, ed., Little “Red Scares”: Anti-communism and Political Repression in the United States, 1921–1946 (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2014). See also Kim E. Nielsen, Un-American Womanhood: Antiradicalism, Antifeminism, and the First Red Scare (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 2001).

(6.) The U.S. Supreme Court upheld a Minneapolis sedition law in 1920. Heale, “Citizens versus Outsiders,” 46–47.

(7.) Heale, “Citizens versus Outsiders,” 53.

(8.) Ellen Schrecker, Many Are the Crimes: McCarthyism in America (Boston: Little, Brown, 1998), 67.

(9.) Heale, “Citizens versus Outsiders”; Theoharis, “The FBI and the Politics of Anti-communism.”

(10.) Schrecker, Many Are the Crimes, 44; Landon R. Y. Storrs, The Second Red Scare and the Unmaking of the New Deal Left (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2012), 53–85, 88.

(11.) Eleanor Bontecou, The Federal Loyalty-Security Program (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1953); and Rebecca Hill, “The History of the Smith Act and the Hatch Act: Anti-communism and the Rise of the Conservative Coalition in Congress,” in Goldstein, ed., Little “Red Scares,” 315–346.

(12.) Dies was not alone; in 1944, Governor John Bricker of Ohio, who was the Republican nominee for vice president, claimed that Communists ran the whole New Deal. Storrs, Second Red Scare, 79–81, 251 (quotation), 287.

(13.) Bontecou, Federal Loyalty-Security Program; Storrs, Second Red Scare.

(14.) Storrs, Second Red Scare (program statistics, 292).

(15.) Storrs, Second Red Scare, 111, 286–292. On the dismissal of homosexuals, see David Johnson, The Lavender Scare: The Cold War Persecution of Gays and Lesbians in the Federal Government (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004).

(16.) Storrs, Second Red Scare. For different interpretation of the relationship between anticommunism and liberalism, see Jennifer Delton, “Rethinking Post–World War II Anticommunism,” Journal of the Historical Society 10, no. 1 (2010), 1–41.

(17.) Ralph S. Brown Jr., Loyalty and Security: Employment Tests in the United States (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1958).

(18.) Larry Ceplair and Steven Englund, The Inquisition in Hollywood: Politics in the Film Community, 1930–1960 (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1980); Victor S. Navasky, Naming Names (New York: Viking, 1980); Patrick McGilligan and Paul Buhle, Tender Comrades: A Backstory of the Hollywood Blacklist (New York: St. Martin’s, 1997); and Gerald Horne, The Final Victim of the Blacklist: John Howard Lawson, Dean of the Hollywood Ten (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006).

(19.) Navasky, Naming Names; Schrecker, Age of McCarthyism, 54–61; and Alice Kessler-Harris, A Difficult Woman: The Challenging Life and Times of Lillian Hellman (New York: Bloomsbury, 2012).

(20.) Robert Justin Goldstein, American Blacklist: The Attorney General’s List of Subversive Organizations(Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2008).

(21.) Storrs, Second Red Scare, 186–189.

(22.) Nelson Lichtenstein, State of the Union: A Century of American Labor (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2003); and Steven Rosswurm, ed., The CIO’s Left-Led Unions (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1992).

(23.) Peters v. Hobby, 349 U.S. 331 (1955); Cole v. Young, 351 U.S. 536 (1956); Green v. McElroy 360 U.S. 474 (1959); and Vitarelli v. Seaton, 359 U.S. 535 (1959). In the early 1950s, by contrast, the U.S. Supreme Court had helped legitimize the Red Scare. Dennis v. United States, 341 U.S. 494 (1951), for example, upheld the Smith Act; Bailey v. Richardson 341 U.S. 918 (1951) affirmed a lower court’s ruling upholding the federal loyalty program.

(24.) Watkins v. United States, 354 U.S. 178 (1957); Yates v. United States, 354 U.S. 298 (1957). See Michal R. Belknap, The Supreme Court under Earl Warren, 1953–1969 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2005); Arthur J. Sabin, In Calmer Times: The Supreme Court and Red Monday (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999); and Robert M. Lichtman, The Supreme Court and McCarthy-Era Repression: One Hundred Decisions (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2012).

(25.) Storrs, Second Red Scare, 203–204.

(26.) Early-21st-century scholarship on COINTELPRO includes David Cunningham, There’s Something Happening Here: The New Left, the Klan, and FBI Counterintelligence (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004), and Seth Rosenfeld, Subversives: The FBI’s War on Student Radicals, and Reagan’s Rise to Power (New York: Picador, 2013).

(27.) Jeff Woods, Black Struggle, Red Scare: Segregation and Anti-communism in the South, 1948–1968(Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2004); and George Lewis, The White South and the Red Menace: Segregationists, Anticommunism, and Massive Resistance, 1945–1965 (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2004).

(28.) For a more comprehensive discussion, see Ellen Schrecker, “Interpreting McCarthyism: A Bibliographical Essay,” in Schrecker, Age of McCarthyism, and Heale, “Beyond the ‘Age of McCarthy.’” Also see John Earl Haynes, Communism and Anti-communism in the United States: An Annotated Guide to Historical Writings (New York: Garland, 1987).

(29.) Richard Hofstadter, Anti-intellectualism in American Life (New York: Knopf, 1963), 41–42. See also his essay, “The Pseudo-conservative Revolt,” in Daniel Bell, ed., The New American Right (New York: Criterion, 1955).

(30.) Earl Latham, The Communist Controversy in Washington: From the New Deal to McCarthy (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1966); and Alan D. Harper, The Politics of Loyalty: The White House and the Communist Issue, 1946–1952 (Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1969).

(31.) See Athan Theoharis, Seeds of Repression: Harry S. Truman and the Origins of McCarthyism (Chicago: Quadrangle, 1971). By contrast, see Richard Gid Powers, Not without Honor: The History of American Anticommunism (New York: Free Press, 1995).

(32.) Kenneth O’Reilly, Hoover and the Un-Americans: The FBI, HUAC, and the Red Menace (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1983); and Athan G. Theoharis and John Stuart Cox, The Boss: J. Edgar Hoover and the Great American Inquisition (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1988).

(33.) Examples include Mark Naison, Communists in Harlem during the Depression (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1983); Maurice Isserman, If I Had a Hammer: The Death of the Old Left and the Birth of the New Left (New York: Basic Books, 1987); Robbie Lieberman, My Song is My Weapon: People’s Songs, American Communism, and the Politics of Culture, 1930–1950 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1989); Kelley, Hammer and Hoe; Randi Storch, Red Chicago: American Communism at Its Grassroots, 1928–35(Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2007); and Glenda Elizabeth Gilmore, Defying Dixie: The Radical Roots of Civil Rights, 1919–1950 (New York: W. W. Norton, 2008).

(34.) Allen Weinstein and Alexander Vassiliev, The Haunted Wood: Soviet Espionage in America—the Stalin Era (New York: Random House, 1999); and John Earl Haynes and Harvey Klehr, Venona: Decoding Soviet Espionage in America (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1999). These findings stimulated a long list of case studies of various spies and alleged spies, including Harry Dexter White, William Remington, Philip and Mary Jane Keeney, and of course Alger Hiss.

(35.) John Earl Haynes, Red Scare or Red Menace? American Communism and Anticommunism in the Cold War Era (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 1996); and Haynes and Klehr, In Denial. Haynes and Klehr acknowledged McCarthyism’s abuses, but bestselling popular interpreters of the new findings did not; see, for example, Ann Coulter, Treason: Liberal Treachery from the Cold War to the War on Terrorism (New York: Three Rivers, 2004); and M. Stanton Evans, Blacklisted by History: The Untold Story of Senator Joe McCarthy and His Fight Against America’s Enemies (New York: Three Rivers, 2009).

(36.) For a discussion of these debates, see Ellen Schrecker, “Soviet Espionage in America: An Oft-Told Tale,” Reviews in American History 38, no. 2 (2010), 355–361.

(37.) For example, John Sbardellati, J. Edgar Hoover Goes to the Movies: The FBI and the Origins of Hollywood’s Cold War (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2012); Athan Theoharis, Chasing Spies: How the FBI Failed in Counterintelligence but Promoted the Politics of McCarthyism in the Cold War Years(Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2002); Goldstein, American Blacklist; Christopher John Gerard, “‘A Program of Cooperation’: The FBI, the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee, and the Communist Issue, 1950–1956” (Ph.D. diss., Marquette University, 1993); Michael J. Ybarra, Washington Gone Crazy: Senator Pat McCarran and the Great American Communist Hunt (Hanover, NH: Steerforth, 2004); Kathryn S. Olmsted, Red Spy Queen: A Biography of Elizabeth Bentley (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002); and Robert M. Lichtman and Ronald D. Cohen, Deadly Farce: Harvey Matusow and the Informer System in the McCarthy Era (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2008).

(38.) Michael J. Heale, McCarthy’s Americans: Red Scare Politics in State and Nation, 1935–1965 (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1998). See also Don E. Carleton, Red Scare! Right-Wing Hysteria, Fifties Fanaticism, and Their Legacy in Texas (Austin: Texas Monthly Press, 1985); Philip Jenkins, The Cold War at Home: The Red Scare in Pennsylvania, 1945–1960 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1999); Don Parson, Making a Better World: Public Housing, the Red Scare, and the Direction of Modern Los Angeles(Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2005); and Colleen Doody, Detroit’s Cold War: The Origins of Postwar Conservatism (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2013).

(39.) Mahoney, “Civil Liberties in Britain during the Cold War”; Ruotsila, British and American Anti-communism before the Cold War; and Luc van Dongen, Stéphanie Roulin, and Giles Scott-Smith, eds., Transnational Anti-communism and the Cold War: Agents, Activities, and Networks (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014).

(40.) Elaine Tyler May, Homeward Bound: American Families in the Cold War Era (New York: Basic Books, 1988); Robert D. Dean, Imperial Brotherhood: Gender and the Making of Cold War Foreign Policy (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2001); Kyle A. Cuordileone, Manhood and American Political Culture in the Cold War (New York: Routledge, 2005); Johnson, Lavender Scare; and Storrs, Second Red Scare.

(41.) Michael J. Heale, American Anticommunism: Combating the Enemy Within, 1830–1970 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1990); Robert Justin Goldstein, Political Repression in Modern America: From 1870 to the Present (Cambridge, MA: Schenkman, 1978); Goldstein, ed., Little “Red Scares”; Alex Goodall, Loyalty and Liberty: American Countersubversion from World War I to the McCarthy Era (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2013); Storrs, Second Red Scare; and Doody, Detroit’s Cold War.

(42.) See Jennifer Luff, Commonsense Anti-communism: Labor and Civil Liberties between the World Wars(Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012); Ruotsila, British and American Anti-communism; and Judy Kutulas, The American Civil Liberties Union and the Making of Modern Liberalism, 1930–1960(Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006).

(43.) A sampling of this early-21st-century work includes, in addition to works cited above, Phillip Deery, Red Apple: Communism and McCarthyism in Cold War New York (New York: Fordham University Press, 2014), on the Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee; Clarence Taylor, Reds at the Blackboard: Communism, Civil Rights, and the New York City Teachers Union (New York: Columbia University Press, 2011); Alan M. Wald, American Night: The Literary Left in the Era of the Cold War (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012); Edward Alwood, Dark Days in the Newsroom: McCarthyism Aimed at the Press(Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2007); David H. Price, Threatening Anthropology: McCarthyism and the FBI’s Surveillance of Activist Anthropologists (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2004); Amy Swerdlow, “The Congress of American Women: Left-Feminist Peace Politics in the Cold War,” in Linda K. Kerber, Alice Kessler-Harris, and Kathryn Kish Sklar, eds., U.S. History As Women’s History: New Feminist Essays (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995), 296–312; Shelton Stromquist, ed., Labor’s Cold War: Local Politics in a Global Context (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2008); Robbie Lieberman and Clarence Lang, eds., Anticommunism and the African American Freedom Movement: “Another Side of the Story” (New York: Palgrave, 2009); Aaron D. Purcell, White Collar Radicals: TVA’s Knoxville Fifteen, the New Deal, and the McCarthy Era (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2009); and Susan L. Brinson, The Red Scare, Politics, and the Federal Communications Commission, 1941–1960(Westport, CT: Praeger, 2004).

(44.) Ellen W. Schrecker, “Archival Sources for the Study of McCarthyism,” Journal of American History75, no. 1 (1988), 197–208.

|

||||

| The spy who made McCarthy | Global | ||||

Like pathologists trying to explain a freak viral outbreak, American historians have been poring over the McCarthyist phenomenon for the past half-century, striving to explain how a small group of legislators, the House Un-American Activities Committee, managed to paralyse US democracy and scar a generation. But the great, ironic secret at the committee’s roots has emerged only now, in Moscow. According to newly unearthed KGB files, the committee’s founding father – the man who paved the way for Senator Joe McCarthy’s witch-hunts – was a Soviet spy.

Advertisement

But to the NKVD (the KGB’s precursor) Dickstein was an important, if troublesome, agent whose mercenary instincts earned him the codename ‘Crook’. For just over two years, at the onset of the second world war, his handlers believed he was worth the money. It was the first and – as far as anyone knows – the last time the Soviet spymasters managed to ‘buy’ a member of Congress.

… we have a small favour to ask. More people are reading the Guardian’s independent, investigative journalism than ever but advertising revenues across the media are falling fast. And unlike many news organisations, we haven’t put up a paywall – we want to keep our journalism as open as we can. So you can see why we need to ask for your help.

The Guardian is editorially independent, meaning we set our own agenda. Our journalism is free from commercial bias and not influenced by billionaire owners, politicians or shareholders. No one edits our Editor. No one steers our opinion. This is important because it enables us to give a voice to the voiceless, challenge the powerful and hold them to account. It’s what makes us different to so many others in the media, at a time when factual, honest reporting is critical. The Guardian’s investigative journalism uncovers unethical behaviour and social injustice, and has brought vital stories to public attention; from Cambridge Analytica, to the Windrush scandal to the Paradise Papers. If everyone who reads our reporting, who likes it, helps to support it, our future would be much more secure. For as little as $1, you can support the Guardian – and it only takes a minute. Thank you.  |

||||

| Edmund A. Walsh – Google Search | ||||

|

||||

| Edmund A. Walsh – Google Search | ||||

|

||||

| fbi time cover – Google Search | ||||

|

||||

| fbi is deeply and secretly antisemitic – Google Search | ||||

|

||||

| fbi is deeply and secretly antisemitic – Google Search | ||||

|

||||

| fbi is deeply and secretly antisemitic – Google Search | ||||

|

||||

| fbi is deeply and secretly antisemitic – Google Search | ||||

|

||||

| fbi is deeply and secretly antisemitic – Google Search | ||||

|

||||

| Trump rewrites history as Russia probe pressure mounts | ||||

Jury deliberations in Paul Manafort’s first (of two) trials are expected to end this week, and whether special counsel Robert Mueller can secure a guilty verdict against the man who led Trump’s campaign will be a pivotal moment for the probe, which Trump continues to attack as a “witch hunt.”